|

Eureka,

N California, October 15/01

Hello,

friends:

Lydia

B's now in northern California, wending her way (in not too great a

hurry, as you may observe) southwards. To the astonishment of our many

good friends at Anglers Anchorage, Brentwood Bay, Victoria BC, the last

dock party really was the last (for the time being, anyway) and we left

Canada on September 17. It was hard to leave after well over two years,

and it's hard to believe. Friday Harbor in Washington's San Juan Islands

was our first United States port of call -- in just a little

apprehension in view of the New York bombings and resultant tightening

of border controls. It was more fear than reality, though. It's often

seemed to me, on previous contacts with US customs, that they don't know

their *rses from their elbows; you get a different story about entry

requirements from each customs official. Understandable, in a way,

because they're doing the immigration department's job, and they admit

they don't really know how. What US officials know, if they aren't

sure about anything else, is how to be aggressive. But we chose

Friday Harbor because it's familiar; they're nice people in the customs

office there and we've never had trouble entering Friday

Harbor before -- and sure enough it went smoothly. We got

Lydia B's cruising permit (she's British registered now) to take

us as far as San Diego. A coy English smile goes a long

way.

So

we set off with big ideas about going quickly to San Francisco after a

first call at Port Townsend, just because it seemed an interesting place

to be, with its long association with traditional boats. (Here's the

main lesson about going long-term cruising -- don't ever tell anyone

when you're going to leave, because it'll turn out to be much, much

later. Repeated dock parties at Brentwood for a non-departed Lydia

B attest to that. And don't tell anyone when you expect to get

there -- there are so many interesting and necessary diversions en

route. If you feel chagrin at all your delays, remember it's

probably a minority who get off the dock!).

Anyway,

at Port Townsend we bumped into another Baba 30 owner, Susan Moffatt,

who wanted to do the SanFran leg with us. She packed aboard more stuff

for an intended week than I brought with me from England for the

forseeable future. Anyway, after a weather delay of several more days at

Neah Bay, an Indian-operated, expensively built and strangely deserted marina just

round the corner before Cape Flattery, we launched into the Pacific

proper one afternoon and immediately got bounced in rough weather. All

the advice in Canada about leaving before the end of August

was probably correct. Late September/October lows are getting deeper and

more frequent and the Pacific high's shrinking positively south now,

taking its comfortable northwesterlies with it. The Washington/Oregon

coast performed as we were warned; the winds were on the heavy side of

manageable, so we got quite big, though short, breaking seas, a boat

rolling endlessly and frequently surfing down the swells with a

following northerly. Much of the time we flew only a staysail, steered

with amazing, tireless precision by the Monitor wind-vane. Rachel

and Susan were sick more or less right away; I never was, fortunately

(though I could have been coaxed with a bacon sandwich, or some such).

So after three days -- making an average of 117 miles a day -- we went

inshore and docked at Coos Bay, Oregon, to get some sleep. Susan had had

enough by then and returned to Port Townsend. The boat's now been

through its paces and we have a sense that she's tough and

dependable. Lydia B then left for Crescent City, our first

Californian port, then on to Eureka -- which must have the best (and

cheapest at US$7.50 a night) publicly-run dock on the Pacific coast.

Everything brand, spanking new, free power and showers -- and free bikes

to explore this fascinating Victorian/Californian town; unclaimed stolen

bikes, courtesy of the local police department. Sometimes it's just hard

to leave.

This

is genuine, west coast America, the heart of the timber -- redwood --

industry and it's fascinating to this new boy (particularly in traffic

on a bike). It's colourful, fast, so-different, zany and (naturally) you

can get anything you want somewhere in town. (That just about describes

the United States; everything is here, and everybody has to have

it). The public buses are painted with flowers and there's a

baby-changing platform in the men's toilet, of course. In an empty car-park

on Sunday afternoon, a man in a car, door open, playing a saxophone. I

notice particularly wealth and poverty side-by-side: up-market shopping

in downtown Eureka, and dossers sleeping in the street round the corner,

on a patch of waste ground next to the Victorian theatre. Pampas grass

growing over the derelict rail-tracks on the business side of town.

There's so much space in north America that when one bit's full or used

up, you step out of the mess and move on to another patch.

Maybe it's an unacknowledged reflection of the way the native Indian

population tends to do things -- the earth reclaims

everything, so leave it lying where you toss it. It's the garbage

god.

You

have to keep an open mind when you travel like this. It's particularly

interesting for a Brit who's lived in Asia and Africa (and rural

Britain, of course) now observing Americans against their native,

plentiful backdrop in the aftermath of the New York events,

confused about why these things should be happening to them.

Americans really are deeply shocked by the terrorist attacks. They've

unified across the board round the slogans and the

collecting-boxes.

We're

now watching the weather for a few days' potential slackening, whereupon

we'll leave for San Francisco -- two days' sail away, given half-decent

winds. We can't go further south than San Diego -- a week's sailing

distant, barring stops -- until well into November because of hurricanes

in lower latitudes. We've done a few boat jobs -- the alternator went

awry at Neah Bay, so we replaced it with the spare, and found a spare

for the spare in a car-breaker's yard, helped by a friendly Mexican

hailing from Puerto Vallarta. The diesel saloon heater developed a leak

(actually, it's been malfunctioning for ages, but a blockage in the

metering jet made it spill out onto the cabin sole, so we finally had to

face facts and deal with it. Which meant borrowing tools from Murray, a

Newfoundlander with Chicago wife Colette on a neighbouring 42-ft

boat called Tarazed; I've since bought similar tools -- that's how the

inventory increases. We've enjoyed several meals with Murray and Colette

aboard each other' boats.

So

it's burritos for supper tonight.

More

anon, and best wishes to you all,

Ian

& Rachel aboard Lydia B.

Lydia B's final leaving party at

Anglers Anchorage, Brentwood Bay, Victoria BC.

Anglers Anchorage, Brentwood

Bay, BC -- Lydia B's home 1999-2001

L - Lowering the Canadian flag

in Haro Strait on the US-Canadian border. R - The bar at Fort Bragg,

northern California.

Cape Mendocino, California. A

place to avoid in onshore weather.

Tues

Nov 6/01, Santa Barbara, California.

Hello,

folks:

Lydia

B is now 1,300 nautical miles out from Canada -- a drop in the ocean, so

to speak, in relation to the distance she still has to go. All this

passing life at sea and periodically on land is fascinating to her

crew, who are in the best stall seats. I'll keep on writing, just to put

it down somewhere -- but if it's causing the faintest yawn for any of

the recipients of these letters, please don't hesitate to say and I'll

trim the address-list accordingly. Although we're necessarily out on our

own, we enjoy keeping in touch as we sail on to new places.

--------------------------

So

-- this comes from Santa Barbara, first stop in the heartland

of southern California. We sped past San Francisco without

acknowledging the sailor's dream -- passing under the Golden Gate --

to make up some of the time lost to difficult weather coming down

Washington and Oregon. We want to be in San Diego, on the border with

Mexico, early November, so we can take off south towards Panama as soon

as the tropical storm season ends in the 10-20 latitudes. We've been

watching the weatherfax pictures on the HF radio/computer, transmitted

by the US Coast Guard. Weather information is everything on a small voyaging

boat. Daily we know a little more about reading the

faxes, alongside VHF weather broadcast continously by the flat

computer voice of NOAA (the American National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration). We hear we'll shortly have a different mechanical

voice.

Fort

Bragg, north of San Francisco, was the last serious harbour bar we

crossed. These constricted Pacific coast harbour entries, with

their heavy, rolling (and sometimes breaking) swells across shoaling

sand bars, are brisk affairs. They take planning and concentration,

usually when you're exhausted with a couple of demanding

nights at sea, with little sleep. There are fewer bars from now on as we

go south.

We

headed across the San Francisco offshore shipping lanes in a

typical dusk fog, thankful for the radar's 16-mile eyes. Fog

is resident on this coast; by now we worry less about sailing blind

on instruments alone. Though having watched the huge hulk of laden

ships crossing our path ahead at 20 knots compared with our five we

took the precaution of calling up San Francisco vessel traffic

service, and the coast guard to let them know we were around.

We

got to Monterey at noon next day and dropped the hook in the bay outside

town. Again, even worse than at Fort Bragg, the noise and stink of

numberless sealions fighting over every square inch of seaside

territory, parking their fat bodies on rocks, dock structures and neglected

boats. They're a protected species here, and they clearly know it.

They're hated by the fishermen up and down this coast, whose lives chasing

tuna, salmon and crab are tough, if lucrative for some. Leave a vacant

space and there's a sealion on it. Their bellowing goes on all night. In

addition the ubiquitous Canada geese, so much part of the sound and

visual scene further north, have by now given way to pelicans.

Monterey's best-known son is the novelist John Steinbeck, whose 'Cannery

Row' is, of course, set in Cannery Row.We bought the book and

walked the walk past the now-demolished sardine canneries. On the whole

though, Monterey seemed a bit overboard in tourist nick-knacks. What's

really interesting about these places is what created them, besides what

keeps them ticking in a current, glitzy world.

Coastal

north California -- maybe like northern parts anywhere -- seemed

down-to-earth, much about work and practical life. Now we're past Point

Conception and going east along the southern California moneybelt. The

rocky shores of further north have given way to sand. Los Angeles and

Hollywood are a stone's throw away. This is bum-watch territory. Not

much sign of struggling industry at the waterside here. First

impressions of Santa Barbara from Lydia B's deck on the narrow harbour

approach through sugar-brown, shoaling sand, steered by red and green

fairway buoys to the acres of masts, is of leisure and comfortable

living. The town-administered marina is packed with over a thousand

pleasure-boats; the relatively few fishing vessels look a bit

token; the many very opulent boats here are just for fun. Lydia B

represents the modest boaters' end. The hillsides visible from

the dock are covered by substantial-looking houses (typically

southern Californian red pan-tiled roofs -- after all, this used to be

Mexico, with Monterey once its capital).

Money

and sun are here in abundance. So are the people. The rat-pack is denser

here than in other parts of the USA; there's a distinct absence of that

laid-back west-coast air we found further north, and especially in

British Columbia. For the first time anywhere we were asked to show

identification for ourselves and the boat, with a warning for good

measure that if we didn't pay the moorage fee within three days, Lydia B

would be seized. Santa Barbara marina office is staffed by gun-packing

cop-patrolmen, keen to explain the guns are reassuring to the

customers. To an English visitor, they seem oddly shocking, especially

when you find a loaded gun sitting next to you in the coffee shop.

In an outdoor shop in Fort Bragg an armed cop was proud to lay

out all the contents of his sagging waist-armoury and explain

them to me one by one: a .33 pistol loaded with nine rounds, two more

clips with nine rounds each, a pair of handcuffs and a large pepper

spray (same size as the one we carry on Lydia. We have no gun, but we do

have a catapult (slingshot) ). But a marina staffed by gun-totin'

cops? Only in America. In fact, maybe only in California.

(Talking

with residents we discover more than a little fear of Santa Barbara's

in-your-face officialdom, and wonder if it goes hand-in-hand with a

money-does-everything culture. Time to leave).

The

cost of living here is much higher than we've met elsewhere. Food -- and

housing -- seem particularly expensive. For the first time -- strangely,

considering the wonderful growing climate -- we found good fruit

and veg at a one-day farmers' market in down-town Santa Barbara. Still,

there's no denying the city is attractive, and clean. Spanish-style

architecture, more and more the norm as we go south, Spanish language

and tall palm trees are the hallmarks. And the warm temperature -- still

in the seventies in November. The electric shuttle bus from the

waterfront to Santa Barbara's extremely attractive central (downtown)

area has no windows -- that's how much rain they expect to get here.

We'll

be on our way tomorow or Tuesday, heading 160 miles south-east for San

Diego, last stop before Mexico.

Bestest

Ian & Rachel

Buying veg at Fort Bragg

farmers' market, northern California.

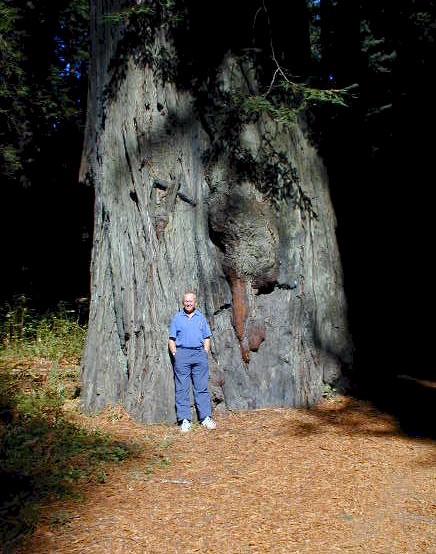

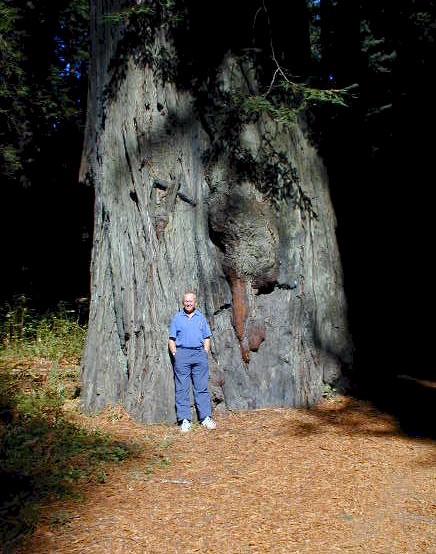

In the Giant Redwood forest,

California.

Giant redwood

Dawn on the dock at San Diego,

southern California.

Cabo San

Lucas, Baja Mexico, Feb 2/02.

Hello, Friends:

Well

-- here we are at last! The long wait in San Diego, Californian outpost

of the safe, known, gringo world, is over. Lydia B has just

rollicked down Baja Mexico, glimpsing whales and gales, and is now

tucked into Cabo San Lucas for the night. We got here in the middle

of the night and anchored in darkness just off the beach of this

fun-and-fajita holiday town, rather than negotiate a strange

new harbour entry when we were depleted with

tiredness. Over the last eight days we've covered over

800 sea-miles. Lydia B's been going like the clappers for Panama

and the Caribbean. Sadly, though we managed a couple of fascinating

overnight stops in the last week or so, and have at

least tasted a flavour of remote, terra cotta Baja,

we haven't had too much time to really smell the roses (as friends back

at base -- Brentwood Bay, Victoria, BC, Canada -- are constantly urging

us). It's a sort of battle between two distinct urges -- the urge

on the one hand to go old-fashioned voyaging in a small, capable boat,

putting sea-mile after sea-mile past our keel because the going is

exciting, and on the other the wish that we could stop and meet more of

the wonderful people we know we're passing by ashore. It might be we'll

never pass this way again -- though that's isn't a thought we spend

too much time on, knowing there are so many fascinating things and

people further down the road. You just have to look at the chart. With

the prevailing wind on our backs we have Costa Rica, El Salvador,

Honduras, Guatemala and the amazing Las Perlas Islands of Panama ahead

of our bow. Then the Caribbean and Cuba.

'We'

on this leg of the journey is myself and Chris, a young Aussie travel

writer from Melbourne whom I met in San Diego. Rachel, who so

far has sailed 3,000 miles with me from British Columbia to the Queen

Charlotte Islands bordering Alaska and down to San Diego, is heading

back to Wisconsin for a couple of months to attend to some personal

things and I hope she'll be rejoining me in Panama. Chris is a great guy

and it's been wonderful letting Lydia's reins out. She's rewarded us

with some great sailing in a whole variety of weather

conditions. The only damage so far has been to the mainsail when

we got caught overnight in a chubasco off Cedros Island -- a fierce

offshore wind generated by heat

and high barometric pressure over desert on the one hand,

and low pressure offshore. We were reefed down to the maximum, but it

still tore the top eight slides from the mainsail luff (the leading edge

of the sail). Seas were, of course, big and ugly -- these things

always happen when you're most tired and longing for a break in the

buffeting -- and we were constrained by having to follow an almost

impossible course through a twelve-mile wide passage between rocks. That

might seem a lot, but from the cockpit of a little boat

in foaming, noisy, wind-torn darkness, it isn't. However,

we did it, marvelled at our prowess and limped along until daybreak with

a loose-luffed main, held only by the halyard and the headboard. Then

after a rollicking, six-to-seven-knot sail for several hours under

headsails alone, still with the land wind hard on our port beam, we got

into a huge, reasonably protected bay -- Turtle Bay -- and were

immediately met in the moonlight by a grey whale broaching 75

yards or so on our port bow. It came towards us -- we were open mouthed

in exhausted awe by this time -- crossed our bow just a few yards

ahead, then came back and broached again right along our port side. We

think these animals, like dolphins, are intelligent. In fact, we rely on

it -- there's nothing we could do if a whale decided to charge us; but

they don't.

Next

day, flying the spare main and having e-mailed San Diego for some

back-up slides and nylon tape, we put out to sea again, going 60 miles

out in search of a dying wind. It died, of course. But the sea always

rewards you. In the glassy calm of the next day we were privy to

everything that moved for miles around. The best catch was a large

school of dolphins in a fun-and-feeding frenzy. It's impossible to deny

that these creatures enjoy life. They couldn't be doing anything else,

with their playful crossing and re-crossing of Lydia B's bow-wave,

sometimes leaping clear of the water. Somehow they communicate their

pleasure to those on board. They leapt, dived and turned over alongside

for us while we photographed them, then came back for another session

when Chris discovered his camera had contained no film. And just for

extra, a turtle lazing on the surface with a passenger bird on its back.

Then we were heading 70 miles out in a straight line for Cabo San Lucas,

right on the rocky end of the Baja promontory 190 nautical miles

southeast. No more drama -- though we escaped running over a

Mexican trawler's fishing nets by no more than 40 yards. He called us on

the VHF and suggested a port-to-port pass -- but since he wasn't showing

any navigation lights, we made a guess -- the wrong one. This is Mexico.

So

today we've had showers, done the laundry and cleaned the toilet and the

kitchen. Two blokes unattended know how to splash the bacon

fat around. We've topped up with diesel, will top up with water

tomorrow, do a small repair to the old mainsail, get some ice, some

fruit and maybe some beer; had an al fresco meal of lobster, beef,

chicken, mahi mahi and Corona by Cabo dockside tonight, nearly got

rooked by a thoroughly entertaining restaurant customer tout (who

is the British guitarist who wrote a song for his dead son?) and will

get on our way south towards mainland, tropical Mexico. Manyana.

More

anon from Lydia B.

Love

& best wishes,

Ian.

Thurs

afternoon: we've now left

Cabo, heading directly for Puerto Vallarta

or further south, if the wind's good.

Sat 0200: --

The wind WAS good. At this moment Lydia B's relaxing at a leisurely 4.8

knots with a flattening sea, moonlight and the remains of an energetic

wind that poured steadily out of the Sea of Cortez as we crossed the 200

miles from Cabo to mainland Mexico. The wind meter rarely fell below 30

knots all Thursday night, raising big, breaking seas that periodically

washed the boat from stem to stern and tumbled over us into the cockpit.

We tied ourselves to the lurching boat. But both the wind and the water

are warm -- we're getting closer to the tropic of Cancer. You have

to marvel at the power of the sea. One second Lydia is slipping off the

top of a new breaking crest as it passes under her keel, her starboard

deck under foaming water as she tumbles at 45 degrees; the next second

she's sliding down into the trough behind the wave crest, and in the

next her eight laden tons are being hoisted 15 or 20 feet like a

weightless toy to the top of the next crest. The air's full of noise and

spray blown from breaking crests. But it's steady on our port beam

and pushes us 100 miles on our way all night, flying only a little

staysail to give us control yet some speed too. Tonight, however,

the only noise -- apart from Chris's snoring in the off-watch sea-berth

below -- is a quiet ripple of water as the port and starboard

streams flowing over the hull combine on the stern to form a modest

wake. Helming is being done by the third crew, the Monitor -- the

dexterous and dependable servo-pendulum self-steering device that needs

only water-power to keep the boat precisely on course. It's time to

sit in the cockpit, watch a sky lit by a haloed, waning moon, then

the first streaks of dawn off the port bow, and have a cup of tea

(we brought about 1,000 tea-bags) and toast with apricot jam. It's the

most amazing thing to be slipping quietly down the

Pacific ocean with a warm breeze pulling Lydia along.

Skipper in the lazarette

This all goes in here? Rachel

stowing stores at San Diego.

Lively day crossing the Sea of

Cortez, Mexico.

Dolphins feeding in the Pacific

off Mexico.

Hot, dry Baja Mexico at Turtle

Bay.

Puerto Angel, Oaxaca, S. Mexico, Tues. Feb 12/02.

Hello,Friends:

You know what they

say -- any puerto in a storm! This one, aptly named, is Puerto Angel,

some 240 miles past Acapulco towards my immediate goal of Panama. It's

on the threshold of the dreadful Gulf of Tehuantepec; I got a sharp

reminder of that fact as Lydia B sailed in around mid-day yesterday, two

days and two nights out of Acapulco.

But wait! There's

another chapter in the crew saga. Chris, who joined me in San Diego for

the leg to the Canal, suddenly left -- I think the term is 'jumped ship'

-- in Acapulco, apparently succumbing to pressure from a girl-friend

back in California. Thanks to the smart, hi-tec system I've installed on

Lydia B, she was able to e-mail him several times a day while we were at

sea. Cry for me, Mexico!

So now it's for

real. I'm single-handing, to Panama at least. There's another 1,000

nautical miles to go -- starting with the Gulf of Tehuantepec just as

soon as I'm sure there's enough of a lull in the northerly gales that

start in the Gulf of Mexico, get compressed through a gap in the Sierra

Madre and burst southwards over the gulf on the Pacific side. It has a

terrible reputation. So I'm studying the weather forecasts and preparing

for the 150-mile dash -- with one foot on the beach, as the advice goes.

Yesterday's entry

into this idyllic little port (a typical southern Mexico village of a

few hundred people) was nothing short of hair-raising. All the way down

from Acapulco conditions at sea were benign, with gentle sailing breezes

by day, more or less flat seas, and calm conditions overnight. By

setting up the radar's watchman zone, which triggers an alarm if

anything enters a designated area, I snatched a few hours' sleep

underway. For entertainment (astonishment, really) I watched a lightning

storm over the Sierra Madre ashore, photographed an amazing

sun-reflection in distant cumulus clouds over the Gulf, saw a large ray

leap clear of the water and flash its white underside at me, and saw

turtle after turtle, floating idly on the surface with no more than its

shell visible, raise its prehistoric head, like a golf ball waiting to

be tee-d off. All this, and steering by the southern cross, a new-found

friend.

But an ominous

heaving of the ocean 25 miles out from Puerto Angel signalled something

new. No waves, just a very long, very big swell coming from the east.

Wind and weather was still benign overhead. It was a sure sign of

something major a long way off in the Gulf of Tehuantepec. By the time

Lydia reached the entrance to Puerto Angel the gloves were off and we

were getting buried in 12 to 15 foot troughs, working hard to keep a

straight line up the 100-yard entry channel. Even though the boat is

still rocking -- sometimes quite wildly -- inside the harbour, it's a

relief to have the hook firmly down. I've never anchored in foam before.

I'll study the

reports of the weather station set up specially for the Gulf before I

make my dash to Madera, on the border with Guatemala.

Meanwhile I've been

getting acquainted with some delightful people in Puerto Angel. First

came an ola! off the side of Lydia yesterday from an official of the

Port Captain's office -- would I please go in the official panga

(universal, beachable Mexican fishing boat) to meet the Port Captain and

do the paperwork? That's an education in itself. This port has no boats

other than pangas -- few cruising boats come here because of the

Tehuantepeckers. But it has an air-conditioned government office staffed

by at least half-a-dozen Mexican officials, in meticulously pressed and

starched white epauletted uniforms with badges of rank, who process

Lydia's entry to Puerto Angel as though it were a 20,000 ton freighter.

I shake hands with Senor Ruiz, the Port Captain, sit down at his desk,

practice my few bits of Spanish and we have a delightfully charming

conversation about who I am, where I'm coming from and going to, why I'm

coming to Puerto Angel etc. "Solo!" he exclaims. He suggests I

write him a letter -- in English -- there and then saying I came into

Puerto Angel because of bad weather. Copy after copy is made of several

documents, passport & ships papers and I'm to take a taxi next

morning to Potchutla, a large town 12 miles inland, to pay at a Mexican

bank for Lydia's entry and exit dues totalling 296 pesos -- about US$30.

I get the strange feeling the Mexicans have been doing this same job the

same way since the conquistadores, with the addition of type-writers,

computers and copying machines, without noticing there's no longer any

job to do. It's so beautiful in Mexico! But on the whole it seems fair

that a Brit, whose nation ambushed so much gold bullion and jewels from

the Port Captain's ancestors in the days of the Spanish Main, should

have to cough up 20 quid for stopping by. If I go to Huatulco, a few

miles nearer the Gulf, I'll have to do this all over again.

So I get up early,

hail a passing fisherman in a panga and hitch a ride ashore. You should

see these people. 100 yards from the steep sandy beach he stops,

reverses slowly, goes forward slowly and gets the rhythm of the beaching

surf. Then he throws the throttle of his 65HP outboard open wide, gets

to 35 or so mph, tells me to get down on the nets and charges for the

beach, tilting the motor as we leave the sea behind. We're now 40 yards

inland, 10 feet higher and the boat's stopped. That's a Mexican panga.

Then it's into a

taxi for Pochutla -- 7 hot bodies in a four-seater, sticky leg stuck to

stranger's sticky leg, careering up and down the mountain, stopping only

for an unexplained military roadblock and umpteen sleeping policemen,

strategically placed nowhere in particular. But Pochutla, a large

agricultural town, is everything I've come travelling for; totally,

exquisitely Mexican and so full of colour and people buying, selling and

being, so far away from European life it's impossible not to see your

own culture in the obverse. I forgot my camera. But really, did I need

it?

I load a bag with

pineapple, oranges, bananas, tomatoes and fresh bread and get another

taxi back, a small, elderly lady sitting on the knee of an elderly man,

total strangers. I find Arturo at the palapa (palm-roofed beach

restaurant) where I ate grilled fish last night and he gives me a panga-ride

back to Lydia. So neat, tidy, expensive and privileged.

I must make time to

get some weather info.

Love & Best

wishes,

Ian.

Lunch on the hoof, soloing off

south Mexico.

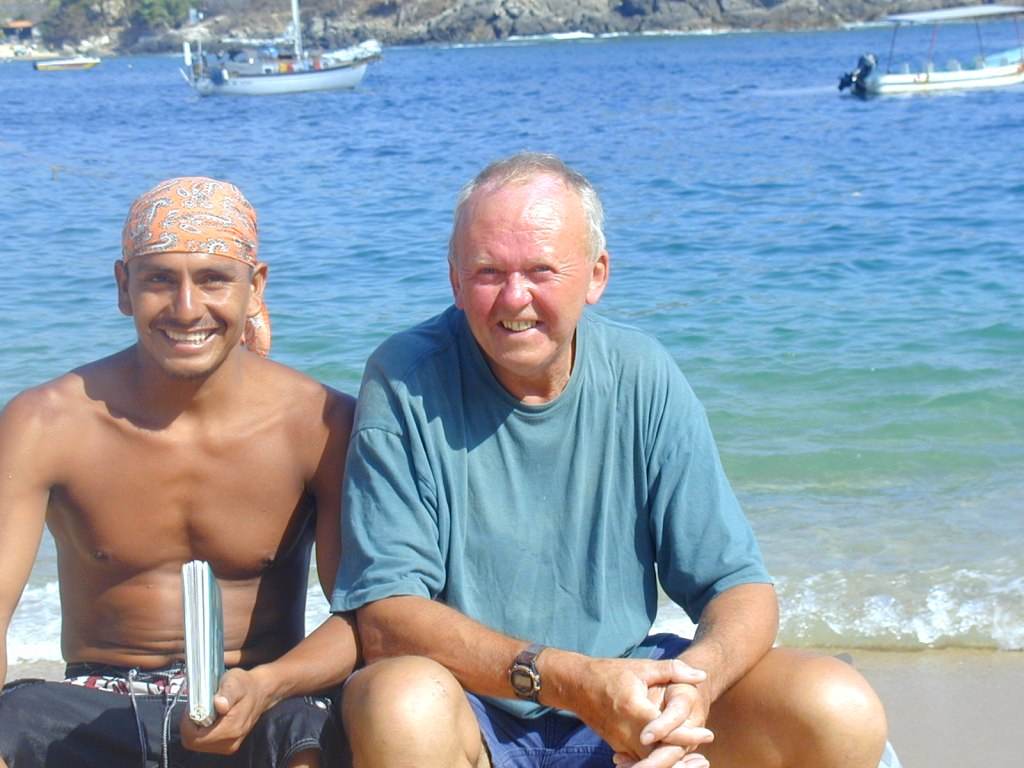

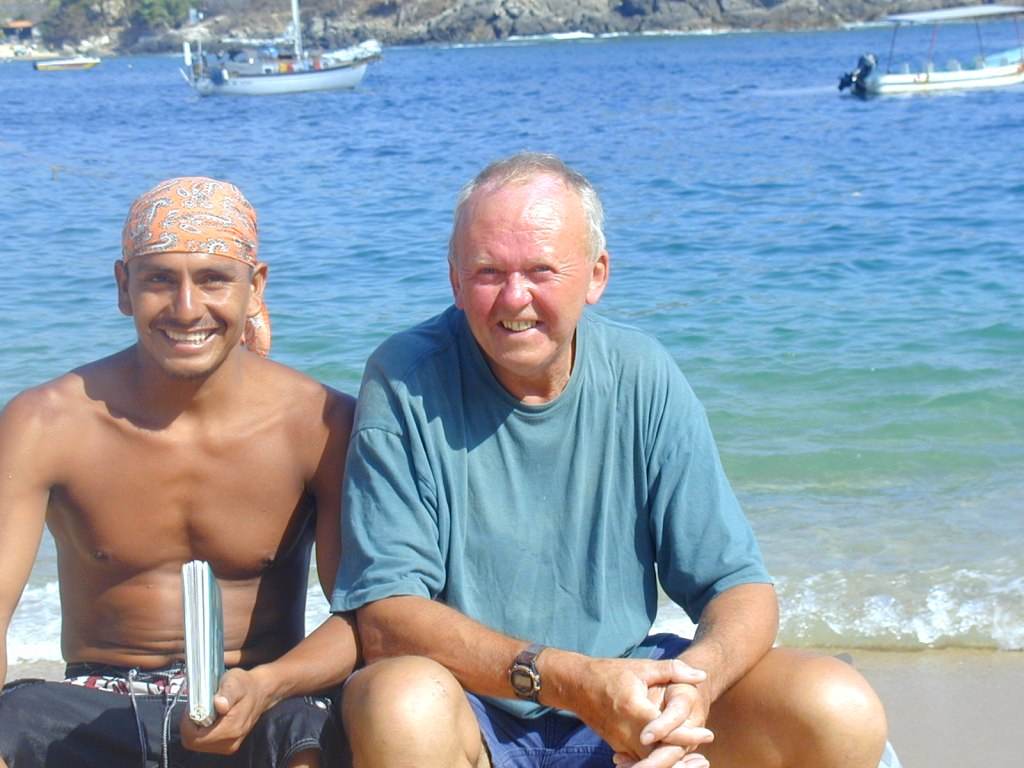

With Mexican panga fisherman at

Puerto Angel, Oaxaca.

Mexican panga fisherman at

Puerto Angel.

Lydia B in a rolling anchorage

at Puerto Angel, Oaxaca, S Mexico.

Puerto Angel, Oaxaca, S Mexico.

Street scene at La Crucecita, S

Mexico

Street kids at La Crucecita, S

Mexico

Sunrise off Acapulco, Mexico

Barillas,

El Salvador, Mar 2/02

Hello

Friends:

It's

just gone five in the morning, it's deliciously cool after punishing

heat yesterday, Lydia B's motionless in still water on a mooring buoy in

the mangroves of El Salvador and all is silent, save for the faint

noise of a generator ashore and the familiar, endless ticking of

shrimps flicking their tails on the boat's hull and the screeching of

monkeys in the trees. I think there are howler monkeys around here. We

-- that is, Lydia and I -- sailed in yesterday after completing the

Tehuantepec crossing and by-passing Guatemala. We rendezvous-ed off

the El Salvador coast with the four other boats we set out from Mexico

with and were led by a local panga past huge, breaking surf

into the lagoon of Bahia Jiquilisco, then through winding, dense

mangroves overlooked by smouldering, active volcanoes -- Usulutan and

San Miguel -- until we came, two hours later, to Barillas. A panga was

waiting to take my bow-line and tie Lydia to a mid-channel buoy in the

fast-ebbing current, so I didn't have to execute the choreographed

panic that single-handers have to go through in these tight

situations, stopping on the buoy exactly the right distance ahead, then

falling back with the current while I put the motor into neutral and run

to the foredeck with a boat-hook. Just as well, because I was fully

stretched after four days at sea.

I

think I'm in a film-set. You know -- one of those

Hollywood B-movies about politico-military plots in banana

republics? (I'm showing my crude, first-world culture -- which, of

course, is precisely why I'm in Central America in my boat, tasting the

real thing).

El

Salvador is one of the most beautiful countries I've been in. The

scenery is quite stunning, from the high mountains of the Sierra Madre

through lush, green jungle to tropical, palm-lined, white

surf beaches. It's a northern European's dream of where in this

world it's nice. But El Salvador is also one of the world's poorest

countries. We saw ordinary life among the villages on the shores as we

sailed in. Houses are not mortgageable here; they're mostly sun-shades,

more than houses, made of sticks and palm-leaves. I was reminded of the

amazing disparities of this world as Lydia, packed with expensive

technical and indulgent goodies (and this is a comparatively modest,

little one -- you should see the others!), passed a family of a man, a

woman and a little girl in a dug-out canoe. They waved cheerfully

and I waved back -- but what a distance!

Here

at Barillas we visiting sailors are lounging in all

the comforts of one of the best marinas I've seen in the whole of

North and Central America. Everything's exquisitely, neatly

organised, from the watered flower gardens, tended grass,

air-conditioned computer-room with a dozen smart new computer-stations,

(I can hook up my own lap-top to send this from one of half-a-dozen

outdoor computer terminals under palm shades in the gardens, then take a

dip in the nearby pool); wonderful hot-and-cold showers, open-air palapa

restaurant. The El Salvadorians are wonderfully,

smilingly friendly. Remember the entry and exit formailities in

Mexico? Here they were done with no fuss, much charm and no dollars by

four uniformed officals who visited and came aboard Lydia shortly

after we arrived. Since I'm a Brit, my visa cost nothing (Americans

pay ten dollars). Today, they're taking us to the town of Usulutan, a

few miles inland, to do some shopping; no charge.

All

this is basically nowhere, in the middle of a swamp. So how does it

work? Who pays for it all? (Not us -- it costs eight dollars a day to

stay here -- though the only money they want is dollars, not their own

colones. El Salvador is phasing out their own currency). I've been

nosing around. The clues (for a B-movie watcher) are the ultra, almost

miltary-style, polish and organisation, and the acres of expensive

equipment and (though very discreetly and still charmingly friendly) one

or two dark-uniformed men with pistols in polished leather hip-belts. El

Salvador has 14 wealthy families, and this has something to with one of

them. Barillas marina club started out in the days -- just past -- when

the families ruled the country. It was a weekend retreat (new

President Flores drops in nowadays with his entourage

for a meal at the Barillas restaurant. He’s a close friend of Juan,

the owner and member of one of the 14 families). Recent social and

military upheaval has turned El Salvador towards democracy and

re-distributed land into farming co-operatives; but wealth has a habit

of re-organising friendships and re-appearing in a different guise. Plus

ca change!!

But

I'm not on a film-set. This is real life in El Salvador. I'm dying to

see how it compares in Usulutan today. Isn't travel fascinating!

Love

& best wishes,

Ian.

Later,

after Usulutan.

Oh,

boy! If you have eyes to see and are in the mood, you could be shocked

by the contrasts in this country. We piled into the air-conditioned

marina bus at 9..0 this morning, exited the steel marina gates after

picking up an armed guard and bounced along a dirt road past sugar-cane

fields fronting the volcanoes for ten miles or so before we reached

the paved highway into Usulutan. We drove through a scene of subsistence

agriculture -- sugar-cane and coffee principally -- and of

mud-and-wattle, iron-roofed shelters that are home to so many of El

Salvador's people, with only the occasional brick house. This really is

a poor country. It's so easy to miss it, whereever you go in the world,

unless you look outside the tourist comfort-zone. US reserve forces

are here -- of course, they're helping to build schools etc.

Anyway,

we did our shopping -- everything is very, very cheap here, though there

seem to be few shortages. I walked with my camera through the

back-streets to the market area. Everywhere I went, people were

friendly, welcoming and rarely refusing to let me take a picture.

Back-street life in everyday El Salvador gives me the same message I got

in Africa and Asia -- that these are tremendous people with small

material goods and a lot to teach visitors from the first world.

The

symbol of El Salvador worn by men is the machete, used to work the

crops. They wear them routinely, fastened to a waist-belt or hanging

from a shoulder, always sheathed in a hand-made, decorative leather

scabbard fringed with leather thongs. I wanted one for a momento of

these people and went in search of a hardware store. The machete was

there alright, and I bought it (for three US dollars and seventy-seven

cents) but not the scabbard. So I stopped a man in the street, admired

his machete and he offered to sell it to me for ten dollars. I'm now a

sailor with two machetes.

L - El Salvadorian boy in

Usulutan fishmarket. R - Orange-seller in Usulutan market, El

Salvador.

Tomato-seller, Usulutan, El

Salvador.

Lunch on the hoof, Usulutan, El

Salvador. Well, it is a milk-bar.

Sugar-field workers, El

Salvador. $3.50 a day.

Salt-pan workers, El Salvador.

$3.50 a day.

Nattering in Usulutan market, El

Salvador

L - Coming home from work in the

sugar-fields, El Salvador R - Tortilla girl (and mum), Usulutan

market, El Salvador.

Line astern up the mangroves to

Barillas, El Salvador.

Contents of the boats that

accompanied Lydia B to Barillas, El Salvador

Bahia Jiquilisco, El Salvador, Thursday March 14/02.

Hello, Friends:

We’re a strange lot, us boaters. We quit jobs and businesses, sell our houses, leave our

families and friends behind, trade security for the uncertainties and

discomforts of the sea in little boats. We’re surely nuts.

But not to a dozen or so families in El Salvador. Just over a year ago,

in January 2001, their homes were destroyed in a major earthquake,

measuring 7.6 on the Richter scale. It was the fifth largest quake to

strike a populated area – and it happened in a country still on its

knees from a guerilla war (remember the Contras?), its already poor

economy struggling. They’re used to disaster here. However beautiful

El Salvador is – and it really is – its people live in volatile

geology, surrounded by active volcanoes.

So what’s this got to do with boats and sailors, and how does into get

into Lydia’s log?

Well, as you gather, I’m still at Barillas in Bahia Jiquilisco

( though I’m doing the formalities for departure for Panama,

and maybe Costa Rica en route, tomorrow morning. I have one more day in

this lovely country).

But to get back to the earthquake.

I spent Monday 3,500 feet up in the mountains, working on a

relief housing project at a little coffee plantation village called

Chiripa, an hour-and-a-half’s drive inland

up steep, narrow and rutted roads – ox-tracks, really

(ox-carts are still common transport round here. Either that or

Shanks’s pony. All the way up you see people carrying water – on

their heads, in wheelbarrows, in ox-carts. There’s plenty of water in

El Salvador, but often you have to go long ways to get it; few houses

have taps. Life’s different here).

The point is that when the earthquake happened, on January

13 last year, a group of cruising sailors had just arrived here

at Barillas. To cut a long story short, they went up into the mountains

to see if they could help, since it wasn’t receiving any aid from the

major relief agencies. The news spread on the boaters’ radio nets,

more arrived with relief goods, cash and labour and the sailors went

right ahead and built six houses at the village of Hacienda Lourdes,

neighbouring Chiripa, each for two families.

The project, still entirely run by more sailors and still entirely

independent of any other relief effort – though it has now been

organized as an official charity, the Barillas Relief Project --

is still going on. Dennis, a sailor

from San Diego, California, arrived -- in a boat appropriately

named Knee Deep – on the tail-end of the first batch of houses and

started another five more or less single-handedly.

He’s staying at least until the five houses are finished and has now

been joined by Neil and his wife, Esther, Canadians from Prince George

and Vancouver, who’ll stay to the end of this phase on their boat,

Paraquina (NB Ron & Colleen – a Saturna 33).

When I was there on Monday, having bounced and clattered up the mountain

in an old Volvo (we put a hole in the petrol tank and stuffed it with

soap, when we got back, to stop the leak), we were putting the finishing

touches to the first of these, helped by local men, women and children.

Though it’s rewarding for us visitors to El Salvador, the work

isn’t easy in the heat (90-100 degrees) and the dust.

The houses are simple, steel-frame structures clad with weatherproof

cement board, entirely non-traditional but built to withstand ground

tremors. They cost a little over US$2,000 each , with three rooms,

earth floor, electricity and no plumbing – but they’re a luxurious

advance on the stick, rusting tin and cloth shacks these families have

been living in since the disaster.

Every penny that’s been collected goes into the houses. The sailors

have dug into their own pockets (helped by $10,000 from the Canadian

government, which bought a diesel generator to power site saws, welder

etc), provided all the labour and there are no administration costs.

Now, although funds have been collected for four of the five new houses,

they need more cash. More land is available if money can be found.

It’s an amazing, unsung story about people.

So, relatively,

we’re pretty well off in our boats. I’ll be sad leaving El Salvador.

Love and best wishes,

Ian.

Farmstead at Chiripa, in El

Salvador's coffee highlands -- scene of the 'quake.

Francisco and Priscilla, owners

of the new house at Chiripa, and (R) their son.

Laying out a section of another

steel-framed house at Chiripa, El Salvador.

Lydia B's skipper lends a hand

at the Chiripa earthquake housing project, El Salvador.

Introduction 0 - Inside Passage and northern British Columbia

2 -

Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama 3

- San Blas to Florida

4

- Intra-Coastal Waterway to Washington DC 5 - Brentwood Bay BC and Chesapeake

6

- Virginia, Atlantic to Azores 7 - Azores, Ireland to England

8

- Chevy through the US - 1 9 - Chevy through the US - 2

|