|

San Andres, Caribbean,

May 22.

Hello, Friends:

It’s early morning and the sky’s a little clearer,

though still with heavy banks of graying cumulus cloud. Yesterday’s

torrential thunderstorm has departed, leaving the air a little fresher,

though it’s still hot and pretty windless. The sea’s

barely rippled. When I’ve finished my pre-breakfast cup of tea I’ll

tune into the SSB weatherfax from the New Orleans tropical prediction center

and see what’s on the cards for tomorrow and the next leg north up the

Caribbean..

San Andres, where we’ve been for the last five days, is

a Colombian-owned island stopping-stone 250 miles north of Panama, on the edge

of the shallow, reef-filled waters off the coast of Nicaragua. It’s a

holiday isle, as the jet-skis that zip around Lydia’s anchorage off the Club

Nautico remind us. Never mind the funfair, though ;

San Andres has ice, which we ran out of over a week ago. Since Lydia B

has no fridge, that’s been the pit of deprivation in these days of 90F and

sticky, energy-sapping humidity. It’s bad enough climbing into a sodden bunk

every night, but to have no cold drinks…..

And San Andres has shops galore – though most of them

are stocked with a strange array of Tommy

Hilfiger fashion clothes mixed with pots, pans and allegedly duty-free TV’s

and washing machines aimed at holiday-makers from the Colombian mainland.

Yes – we’re now on the Atlantic side of the Panama

Canal, heading for Florida and the US east coast, looking over our shoulder

for the first signs of the hurricane season on our tail. Strings of tropical

waves marching from east to west further south below us – the first signs of

future cyclonic weather activity – remind us not to dally. We’re about a

month behind schedule. Not too bad in the way of things, as most sailors would

tell you. But I’ll be happier when we’ve got the next 800 miles behind us

and we’re within spitting distance of hurricane protection on the US

mainland.

So – Rachel newly back from Wisconsin -- we finally

transited the canal after two week’s delay at Balboa. Hung with old car

tyres for protection in the locks alongside the fearsome big ships, and

weighed down with four extra hired line-handlers, two Canal Authority advisers

(a pilot and his understudy), plus cold drinks and hot curry ready for lunch

for all aboard en route, we got through the three sets of locks and two lakes

– 50 miles from Pacific to Atlantic – in the day and without mishap. From

the astonishing engineering seen from above and from the bottom of the locks

to the crocodile on the mudbank, the monkeys in the trees and the

strange birds aloft, it was – for US$650 and much nail-chewing – a

ringside seat at a truly amazing show.

A few fly-ridden days anchored at Cristobal, and having

ventured as far as the post office in Colon -- school for half the world’s

muggers by all accounts -- then

Lydia headed out against the westbound tradewinds

to go to the San Blas islands, 70 miles east of the canal and home to

the Kuna Indian people. It’s hard to describe San Blas in a couple of

sentences; but they’d have include the clearest water we’ve ever seen,

coral and amazing underwater fish life, coconut palms and white sand just like

the Bounty bar ad, lovely, friendly people, lobster galore – and molas.

Molas are the colourful, hand-sewn patchwork fabrics

depicting Kuna life that are still worn by all the Kuna women, and which they

are adept at selling to visiting boats, sometimes with a little barter trade

for coffee, milk powder, soap and such. Their craftsmanship is high, and we

must now have a collection of a score or so to add to the Woonan indian

carvings, shells, cocabola timber etc that now cram Lydia’s dwindling space.

Sadly, my digital camera went the way of so many things

electronic on the rough, two-day sail from San Blas to San Andres. Lydia got

thrown about and sea-water dripped into the quarter-berth, scoring a hit on

the faithful Olympus when it rolled out of its bag. I have e-mailable pictures

up to San Andres, but from now on it’s back to the old 35mm.

Today we’ll decide on the next leg of the passage

north.We’re still with Indara, the boat from Washington state we met way

back in Pacific Mexico; and there are new buddies

now – Dalliance and Restless, both heading for the United States.

They’re 35 and 37-footers, so Lydia’s still the baby of the bunch. Next

stop Isla Mujeres in the Mexican Yucatan.

Love & best wishes,

Ian & Rachel,

Lydia B.

Chichime, San Blas Islands, Panama.

Kuna Indian girl, Chichime, San Blas,

Panama

Reefed. Hallberg Rassy stuck and

stripped in San Blas, Panama.

Laundry day mid-Caribbean.

Mid-Caribbean passenger

Loading water at Isla Mujeres,

Caribbean Mexico.

|

Isla Mujeres, Yucatan, Mexico, June 3/02.

N21.14, W086.44.

Hello, Friends:

We’re back in Mexico. After the long haul down

the desolate Baja and Mexico’s

Pacific coast

in January & February, this is a fleeting glimpse of a different Mexican face, the Caribbean one. We’re in the

land of the Mayas. The place is different, and so are the people.

We’re also in holiday-ville. We can see Cancun,

one of the world’s major package tourist traps,

a few miles ashore

from Lydia B’s island anchorage. All day the fast and slow ferries

bundle visitors in and out of Isla Mujeres to spend

their pesos and dollars in the mile or so of narrow streets that

seem to contain little else but tourist trinket shops – woven fabrics,

silver jewellery

and the renowned Yucatan hammocks. We joined the throng

and bought our share. We now

have a hammock each, to string between the

forestay and the shrouds and hang around Mexican style. They’re

old-fashioned ones, made of woven hemp. We even bought a shark’s-tooth

necklace -- though we have our own shark’s teeth, taken from a dead

hammerhead shark

beached at Cayo Vivorillo, our last idyllic coral

island stop 400 miles or so back.

By now, of course, we’re less than 400 miles from

the United States – and 100 miles from Cuba. And nearly 6,000 miles

from Vancouver Island, British Columbia, where Lydia B started her

voyage down the Pacific last September. Central America and the Panama

Canal are nearly

behind us and our own culture beckons again. We’re

already mentally changing gear, and wondering apprehensively how we’ll

take to the different way of life. We’ve filled up again with water,

stores and diesel – slack winds and calm seas in this period between

the strong Caribbean tradewinds

and the arrival of the hurricane season

means we’ve had to use the iron genny a good deal.

Already the squalls are increasing and tropical

waves, birthplace of future seasonal hurricanes, are marching westwards

across the Atlantic to the southern Caribbean just above the Equator.

They’ll creep north as the summer advances, until by August they’ll

spawn cyclones. We’re pretty safe

yet, but it’s an uncomfortable

feeling and we want to be on our way. We’ll feel safer when we reach

the Chesapeake, north of the Carolinas and another 1,500 miles or so

from here. We’ll sail for Key West, Florida, later today.

Meanwhile Lydia B has used up one of her nine

lives. (We’re confident that like cats, boats have these). Half-way

between Cayo Vivorillo and Isla Mujeres, 120 miles out into the

Caribbean, a through-hull fitting – the one containing the knot-meter

– collapsed, leaving an inch-and-a-quarter hole in the hull two feet

below water-level. By sheer chance, we were on the spot when it happened

and got a wooden bung in before much water flooded in.

For a brief, chastening moment we were looking at

undersea sunlight through a hole in the boat. It was one of those

traumatic occasions when much time passes in split seconds. We’re now

examining the remains of the through-hull to see why it happened. The

bung will stay in place, safely, we think, until Lydia comes out of the

water in the US and we can make a permanent

repair. Ask us now if we

believe in good fairies.

We’re a bit behind with pictures. These cover

Lydia B’s transit of the Panama Canal and ten days or so in the San

Blas Islands before we set out on the passage north from Panama.

Love & Best wishes,

Ian & Rachel,

Lydia B.

Lydia B anchored at Chichime,

San Blas, Panama.

Kuna Indian girls getting

goodies from Lydia B, Chichime, San Blas, Panama.

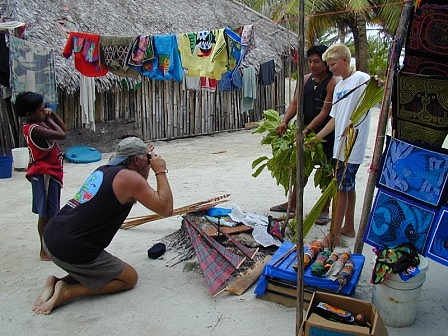

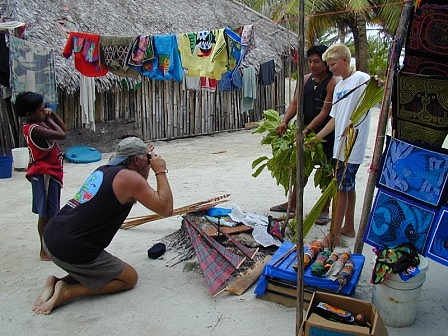

L - Richard, Kuna Indian baker,

baking the day's bread buns at Chichime, San Blas. R - Eric and

Kuna mola-maker.

Cruising friends at Chichime,

San Blas.

Kuna Indian family and dugout

canoe, Chichime, San Blas.

Kuna Indian mola-maker, Chichime,

San Blas.

Kuna Indian ulu -- sail-powered

dugout canoe -- at Chichime, San Blas.

Hollandaise key, San Blas

islands, Panama.

With hammerhead shark and Kai at

the Caribbean atoll of Cayo Vavarillo.

Lydia B anchored at Isla Mujeres,

Caribbean Mexico.

Nassau,

Bahamas, Tuesday, June 11/02

Hello,

Friends,

They

say events are character-forming. I’m writing this on my lap-top in

the departure lounge of Nassau airport. That’s right -- Nassau in the

Bahamas. I should be in Key West, Florida at the nav table on Lydia B,

where all the rest of these Lydialog chapters

have

been written.

I’m on my way home (to Lydia, that is) after traumatic events in the

last three days. Briefly, your skipper was brusquely ejected from the US

of A within 36 hours of arriving at Key West, Florida by a gun-toting,

hard-staring, deaf-to-any-appeal blonde lady representing the

teeth of

the feared American immigration service.

I’m now a wrong-doer with a finger-printed record. I was stood

up against a brown immigration office door and mug-shot like the wanted

September 11 New York bombers whose photos adorn the adjacent wall of

the same office. If I wasn’t a journalist looking for good copy, I’d

be

stung. Right now I’m on mental overdrive, tired, a bit miffed and

non-plussed. Thank goodness I’m not a criminal. Or maybe I am?

But

let me go back a bit, because the last you heard from Lydia B was from

Isla Mujeres, island outpost of the Mexican Yucatan. We left there last

Thursday afternoon, taking advantage of a coming break in the series of

Caribbean thunder squalls that will from

now on increase until

full-scale hurricanes arrive from sometime soon until November.

They

give them nice, cosy names like Henrietta and George, but there’s very

little that’s

cosy about them. The first two or three days were quiet

as Lydia B sailed and motored in

a near-absence of wind across the Yucatan Straight, then 50 miles off

the northwest coast of Cuba. Currents were supposed to be with us, but

we never found them. As we entered

the Florida Straight and neared Key

West on Sunday night we switched onto the newly within-range VHF weather

broadcasts of the United States National Oceanographic and Atmospheric

Administration (NOAA). NOAA does a great job of forecasting weather for

sailors, and it’s been good to be back listening to that stacatto,

automated voice out at sea. You get to like it as the voice of a

slightly retarded but very helpful friend.

Anyway,

we could see on Lydia’s port bow a building mass of black cloud over

the Florida Keys and knew something was brewing. In the night-time

darnkness these clouds look sinister and unreal. They have an ominous

shape, billowing grey-black, blotting out the

stars that reassure us we’re

going in the right direction, dense rain-squalls shafting to sea-level

which we pick up on the radar. Sometimes you can see them far enough

ahead to steer round them. Sometimes they’re so big and develop so

quickly you can’t get out of the way. Next we were listening to a

special NOAA storm warning of gale-force winds, deadly lightning

strikes, very heavy rain and waterspouts. Already tired after three

nights at sea, we battened down for an onslaught, reefing just in time

before it hit us.

Our

only hope was that the storm was moving west. We were towards its

eastern end, and moving north-east, though battling a 3-knot west-going

current counter to the infant Gulf Stream emerging the Gulf of Mexico.

But these storms are generally short-lived and we were lucky. The bulk

of it crossed Lydia’s bow and we escaped with a lashing from its

eastern edge, illuminated by immense lightning flashes. We got thrown

about a bit.

One entire bookshelf disgorged itself onto the cabin floor and

salt somehow penetrated where there was no conceivable way in. But we

emerged safely into daylight ten miles south of the

main shipping

channel into Key West. The sun rose, Lydia shook out her mainsail reefs,

flew her yankee headsail again and galloped up the bright, buoyed

channel through water pale blue from sky and sand, alongside a

big white cruise ship heading for Key West to disgorge yet another load

of overnight trippers. They

lined the rails to photograph Lydia as the ship overtook us. Did they

wish they were sailing on our adventurous little boat rather than the

big, comfortable liner?

Pretty

well exhausted, we dropped the hook off Wisteria Island opposite town,

called up

the US coastguard on the VHF to ask about entry formalities to

the United States and – well, that’s when things took off.

Clearance

formalities are done with the US Customs, who issue a cruising permit

for the boat, with the Department of Agriculture who vet incoming fruit

and veg (we surrendered all

ours – Mexican oranges, onions, tomatoes and garlic); and with the

Department of Immigration, who guard the many scattered gates of this

immense, cosmopolitan country against undesirable intruders. They do

their job with the unsmiling, unsentimental,

unhearing dedication of a

pack of Weimaraners. It’s the cold unsmilingness that hits a lazy,

laissez-faire English person like me. It’s struck me with sudden

clarity, three years into North American life, that there really is a

difference between national cultures, and it’s to be

found somewhere,

chillingly, here. In the last few days I’ve felt a new affinity with

my European – I think it’s that, not just English – roots.

So

here I am, newly arrived in America – with US citizen Rachel

alongside, knocking on the immigration office door, passport ingenuously

in hand, voluntarily reporting our arrival in

the United States and

seeking permission to cruise up the East coast. On the other side of

the

split, counter-top door is a woman in white T-shirt with INS INSPECTOR

in big letters on the back, macho navy blue heavy cotton shorts

festooned with bulging patch pockets

and crotch creases and white,

turned-up running shoes. She has straight, blonde hair and

I’d guess

is about early forties. Her waist is hung with a stiff black leather

belt containing holstered revolver (soon I haven’t the faintest doubt

she’d use it), several ammunition pouches, cell-phone (or phones) and

gas or pepper spray. I can’t quite decide if her look is mean or

worried. I’m scrutinizing her for evidence of femininity. Her posture

is more that of

a hunting male panther, with dandruff. She doesn’t

walk; she swaggers to impress.

So

far, I haven’t a clue what’s about to happen. Panther-woman keeps

our passports. Rachel’s

is cleared, but not mine, though she doesn’t hand it back to Rachel

yet. Stapled inside mine is a US 90-day visa-waiver from August 2001,

which I should have handed in when I left the USA on the way down the

Pacific coast from Canada to Mexico. I didn’t, so (says panther lady)

I was illegally in the United States from mid-November to January 21,

when I sailed south from California. Quite erroneously, the valid

six-month cruising permit issued in Washington State, way back up the

Pacific, had managed to convince me my presence was legal. More than

this, says panther lady, I didn’t have a current visa to

re-enter the

United States. (British citizens don’t need one, but I discover they

do if they

arrive by private boat. If they’re heard at all, these

rules are whispered, not shouted).

Panther lady

steps aside to make out-of-earshot phone calls to head office, returns

and announces I have to leave the country immediately.

I

can choose either to leave on Lydia B, given a few hours to re-provision

and escorted to the 12-mile limit by the US coast guard, or I can fly

out of the country. ‘But my boat; it’s my home….?’ – ‘You

WILL be leaving by tomorrow night….’ Not a trace of sympathy, no

feminine softness. This lady’s in command of the trees.

It

takes a while for things like this to sink in, back on Lydia B, anchored

just off town, overnight. I keep thinking: they just want to scare me.

We’ll go in tomorrow and they’ll

wag a stern finger and say they’ve

decided to issue a visa after all. They’ll see I’m a

harmless

pensioner.

In

the morning we’re again chasing up flights to Nassau on the internet,

car hire

companies for the drive from Key West to Miami, Greyhound buses

and the US Embassy in Nassau. Will I get a visa quickly – or at all?

Isn’t there an outside chance I won’t be

allowed back into the

United States and I’ll be parted for good from Lydia B, left with

Rachel alone on board? What then? Panther woman has neither guarantees

nor visible concern. I keep asking questions, meekly suggesting that

although I accept I’ve broken

the rules, I haven’t done much harm.

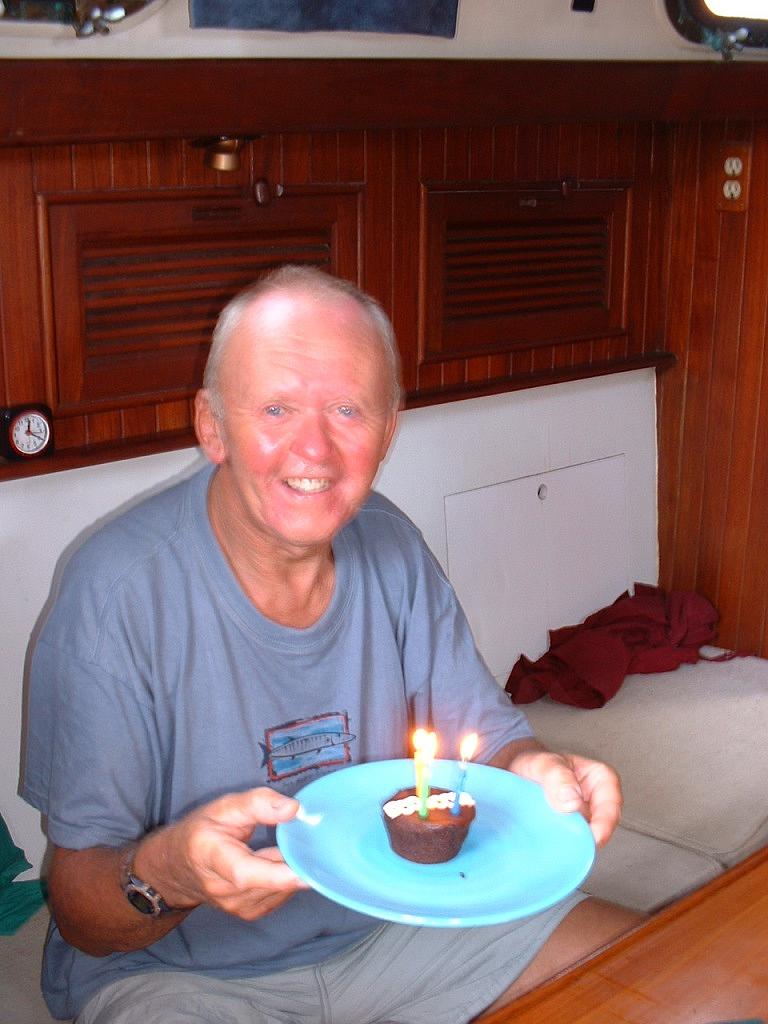

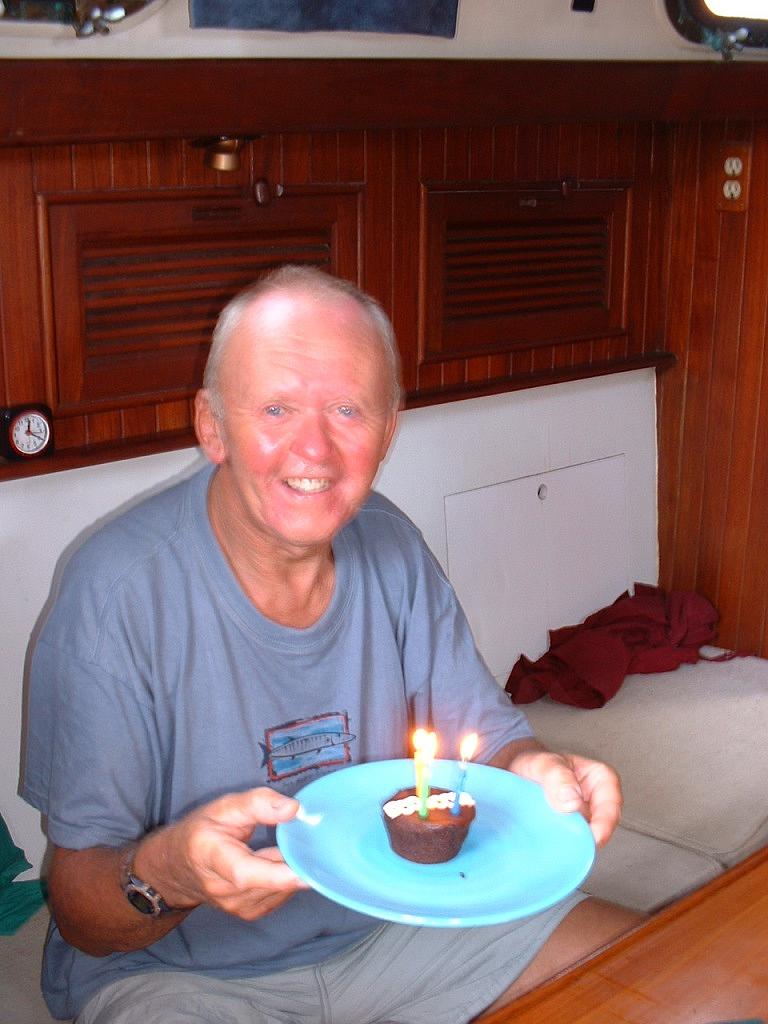

Goodness, I’m a pensioner these last four days, fresh from my 65th

birthday at sea. Panther-woman pokes her face at me and warns me –

B-movie-style – she’s getting upset. That’s the last thing, I

guess, you want to make an immigration inpector do. I shut up.

At

last we find a flight from Miami to Nassau and book it. I have to pay

for it when I get to Miami airport. Not good enough, says Ms immigration

lady. She phones the airline herself. I have to pay for the flight

before I leave Key West. She wants to see the ticket. Can’t, says the

airline. Go and find a local travel agent, says the blonde panther; book

it again. Which we do, then return and show her the ticket. Then, having

hired a car and tossed a few things into a back-pack, we abandon Lydia B

on her anchor-chain and drive to Miami, Rachel at the wheel. It’s a

beautiful drive up the Florida Keys. But is this the last time I’ll

see

it – or Lydia B? Of course not. I’m dramatizing. Which is

exactly what you do in these circumstances.

Soon

I’m in the air, then I’m giving my late-night story to the Bahamian

immigration service at Nassau airport. There’s a problem -- there’s

no US stamp in my passport to account for

my provenance. The Bahamians

sympathise, are friendly and give me ten days to get the

US visa. An

officer finds me somewhere to stay. I bed down after midnight in a

seedy,

empty hotel – “under new management” (though that seems to

be a total staff of one mildly-spoken, polite Indian gentleman from, he

says, Madras. Don’t tell me any more that national cultures aren’t

different.) near the centre of Nassau, just round the corner from the

American embassy. No tea, but I manage to get a cup of lukewarm coffee

and a shower. The Hilton’s on the opposite side of the road. But the

sheets are clean – and anyway, I’m bushed.

In

the morning as I’m collecting up my overnight things there’s a huge

thunderstorm. Nassau roads are awash. I’ll get drenched on the

200-yard walk to the embassy. It isn’t a very encouraging self-image.

I see myself dripping onto the embassy carpet, belongings in

a white

cloth shopping bag, pleading to be let into the United States. They’ll

already have seen my criminal record on the computer. Panther lady will

have made sure. I’m tired, hungry, homeless and disorientated, like

the bag-lady on the streets of London.

I

get to the visa application office five minutes before official opening

time, open the door – and an confronted by a sea of queueing Bahamians

all after the same vital piece of paper as me. It’s going to take ages

to deal with all these people. My hopes for a return to Miami on the

five o’clock flight that afternoon plummet. Or is it just because I’m

tired and short of food? I fill in the visa form and hand it in with $65

dollars. Yesterday it was $45; it’s gone up just because I’m bad. In

answer to the form’s question ‘Have you ever been refused entry to

the United States?’ I say ‘yes’.

There’s

a 20-minute wait. The Bahamians seem to be getting their visas and

leaving one by one. No word of mine. I’ll never see Lydia again. Then

a female voice comes over the loudspeaker – ‘Ian Laval. Please go to

window three.’

It’s

an older State Department official. She has my forms. But she’s

smiling. How I need that smile! She asks what I’m doing in North

America. Sailing a boat from British Columbia to England, I say. She

smiles again. I gobble it up. She points to my answer about being

refused entry, and I recount the previous two days’ events at the Key

West immigration office. She checks the computer and seems already to

know. ‘Why…….?’ she begins, then pauses and seems to want to

tell me she’s surprised I was summarily thrown out. She can’t, of

course. Then, pointing to my Cumbrian origins on the application form

– “ Do you know Carlisle Castle? I was there two years ago. I was

posted to the embassy in London”. Crisis over. My hopes soar. Somebody’s

human. My visa is ready ten minutes later and I walk out onto the

streets of central Nassau. There are still huge puddles, but the rain’s

stopped. I’m

in a typical English town, where traffic drives on the

left and friendly, white-jacketed policemen,

with no guns, saunter in pairs along the pavements of The Bay, the main

shopping street. I’m no longer a bag-lady. Somebody wants me.

I

have a beer and a burger at the Pirate Bar and make the airport in

plenty of time for the 5.0pm back to Miami. It’s delayed an hour –

but what does that matter? I’ve e-mailed Rachel, who’s driving the

140 miles again from Key West to meet me, having dealt the previous

night with her own crisis aboard Lydia. A Canadian boat dragged its

anchor and drifted into Lydia’s bow, being stopped just after

colliding with Lydia’s bowsprit. Lydia took it on the chin. There’s

no damage, except to nerves.

We’re

back on Lydia by midnight. Legitimate.

Key West,

Saturday, June 15.

Strong

southerly winds and heavy rain continue and Lydia’s bouncing around on

her anchor-chain.We’ve had another wicked line-squall this afternoon.

Torrential rain driven by a 40-knot wind blotted out virtually all

visibility. Caught in a strong tidal current at her anchorage off Key

West, Lydia didn’t know which way to point, to the wind or the stream,

and we stood ready in case she waltzed her anchor out of the sand. But

she didn’t. The thunder’s still rolling around.

In

the next couple of days we’ll take a last look round this attractive

sub-tropical town,

with its streets of well-kept, white wooden houses,

green trees and busy pleasure-dock

scene and get ready to leave

northwards up Florida as soon as this weather lifts. Key West’s

atmosphere belies that of the US immigration service and Panther lady.

She asked – I don’t know how anxiously – if I’d be writing about

it. Yes, I said. But I’d try to be fair.

Love &

best wishes

Ian & Rachel,

Lydia B.

Rachel raises the US courtesy flag off Key West, Florida.

L - seniority cake, mid-Caribbean. R - Flying fish

scores a bulls-eye in Lydia B's scupper.

Fish and chip shop, Key West, Florida.

Sunset off west Cuba.

Vero Beach, Florida, Saturday June

22/02.

Hello, Friends:

Feeling a bit poor and want to know where all your

money went? Take a look down here.

Lydia B’s now sailing (chiefly with

the iron genny, that is) up the Intra-Coastal Waterway, a sort

of ditch

inside the US east coast that takes you in relative safety from the

weather as far as North Carolina and the Chesapeake. I’d call it a

canal, but that gives no impression of the mind-boggling private wealth

lining its southern banks. The buildings and boats you pass for hundreds

of Florida miles are anything but derelict industrial warehouses and

rusting coal-barges.

The glitz began at Miami, where we

arrived at the end of a tough, offshore passage from Key West, riding

the Gulf Stream flowing north-east outside the reef that guards the

southern tip of this orange-growing holiday state. Short of somewhere to

anchor, we tied up at a marina beneath the sky-gazing hotel blocks of

Miami Beach. Clean, white concrete (even if it was behind locked

security gates), someone to take a line as we approached and tied up

Mediterranean-style

between wooden piles, a shower ashore for the first

time in ages – we’ve been so long at sea,

living continuously with

sticky sweat. And a deli a few yards away for coffee and a croissant

next morning before pulling out, past the city-centre dockyards, the

maze of route marker posts – red triangles to port, green squares to

starboard – on up the ICW. It’s all so different.

Across a confusing waterway junction

in downtown Miami, Lydia B pushed through town by

wind and tide,

searching for the correct exit before we miss it and all the time

watching the depth gauge – shoals and shallow water in the ICW are the

daily problem now – and soon we’re rounding the bend to the

Rickenbacker Highway Bridge, with a main-road span 76 feet over the

water – plenty of height for Lydia B – then the Venetian Causeway

highway bridge, the first of dozens of lifting bridges (mostly bascule

and double bascule, as they’re correctly called). We call the

bridge-keeper up on VHF channel 9 and ask him or her to let us past. “Come

right on down and we’ll get you through.”

We say a “thankyou. Lydia B standing by zero nine.” We’ve

by now got our radio patter pretty sharp. Bells clang, road barriers

come down, traffic stops – country

lane or Highway Route 1, it makes

no difference – the bridge lifts and Lydia B, all 50 feet of her from

sea to mast-top radio aerial go through the bridge and we call a radio

thanks or wave to the keeper looking down from the turret before there’s

another bell-clanging and the bridge closes. It works like clockwork,

even for this insignificant little ship. This is America.

So far we’ve touched bottom only

once, pushed aside by a speeding powerboat that bounced us with its wake

and dropped Lydia B onto her bottom as we edged out of the way to the

side of the channel. But the bottom’s soft mud and it was a gentle

reminder not to be so English polite. As I say, this is America.

Vero Beach, where we are now, is a

typical, municipally-owned marina. We’re on a mooring

buoy for eight

dollars a night – though we have the use of showers and washing

machines etc ashore, plus unlimited access to midges (no-see-ums) from

the neighbouring mangroves. They

pack a fearful punch and just love this

still, damp air, so we’ve got bug-netting up and a citronella candle

in the cockpit. In fact it’s critter-ville on Lydia B at the moment.

We’ve had an infestation

of cockroaches, probably brought aboard with

the groceries. Swatting them’s a waste of time – they’re greased

lightning and seem to be able to tune into your attack mode before you

can lift a hand. So we’ve got cotton-wool balls soaked in insecticide

in locker-bottoms, plus a dozen roach hotels stuck up round the boat.

The idea is that they scurry out for a quick meal and don’t live to

regret it. I think we might be winning.

We’ve got rid of our accumulated

rubbish (garbage) – a constant problem on a travelling boat (that’s

‘traveling’ to North Americans. Even the language is different). We’ll

fill up with diesel and water (no longer having to worry if the water’s

drinkable. It’s America), empty the sewage holding tank (which we

usually do out at sea, but not in the ICW, where it’s illegal anyway)

at the marina pump-out and be on our way northwards tomorrow. Soon we’ll

be in Georgia, then the Carolinas, North and South, listening intently

to NOAA weather radio for the possibility of cyclonic weather in the distance and keeping an eye open for

bolt-holes to batten down in. They take hurricanes seriously round here.

I’ll be glad to reach the Chesapeake.

Love & best wishes,

Ian & Rachel.

Lydia B enters downtown Miami and

the Intra-Coastal Waterway (ICW).

L - Double-bascule bridge opens on

the ICW for Lydia B. R - Rachel steers into the ICW.

Nice little place. One of

thousands on the ICW in Florida.

Life in the fast lane on the ICW.

Introduction 0

- Inside Passage and northern British Columbia

1

- British Columbia to El Salvador 2 -

Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama

4

- Intra-Coastal Waterway to Washington DC

5 - Brentwood Bay BC and Chesapeake

6

- Virginia & Atlantic to Azores

7 - Azores, Ireland

& England

8

- Chevy through the US - 1 9

- Chevy through the US - 2

|

|