|

Grand Canyon, Arizona, Thurs. Hello, Friends: If ever you thought Americans didn't have a sense of humour, try travelling Arizona's Route 66. That's the back road -- the first federally-built highway -- that migrating thousands took from Oklahoma to California over a century ago. These days it's sidelined by Interstate 40; but what a feast it misses! Route 66, you remember, is where you get your kicks (was it Nat King Cole who sang that?). Right now I'm basking in flawless Arizona sunshine in a carpark 7,000 feet up on Grand Canyon's south rim, legs recovering from Tuesday and Wednesday's trek to the bottom of the canyon. As I emerged last night, no more sweat left to sweat, a group of kids who'd done the same 20-mile, 4,500ft slog down and up again ahead of me chorused congratulations. They looked puzzled when I returned the compliment. A whisky and ginger back in the Chevy's rarely gone down more easily. Needless to say the astounding beauty of the inner canyon overwhelms the pain of the extreme effort needed to get to the Colorado River on foot, along steep tracks that you start off along in ice crampons, past brilliant sandstone canyon walls and desert vegetation and sometimes cling precariously to cliff edges from which there's a sheer drop into the muddy river. Were it not for the steak that awaited me at Phantom Ranch at 5.0pm on Tuesday -- and not a minute later -- I might have flinched at this tight-rope stuff, and the bouncing suspension bridge that gets you, pretty tired by this stage, 100ft high across the Colorado. Then, after a night in the bunkhouse, a repeat performance upwards -- seven and a half hours up, against my four hours down. Cactus, cottonwood trees, ravens, deer, bird, plant and animal-life galore -- the canyon-bottom abounds with life invisible from the top. And all against a sky faultlessly blue for the past two weeks. But to go back a bit, and that $10 bet I agreed to place in Las Vegas before I left Nevada. I emerged from my day at the Sunset Station casino, an enormous gambling spot in the east of this gambling mecca, exactly one dollar and 25 cents down. But the unlimited food they provide -- American, Mexican, Indian, Chinese (you name it) to keep the punters punting all day and all night put me well into profit. Besides you never have far to go in America to get from the ridiculous to the sublime. Next day I'm on the short hop to the Hoover dam, half of which is on Nevada side of the Colorado and half on the Arizona side. One minute you're in a bawdy city-of-all-cities, next minute you're looking at an astonishing American engineering feat and work of art of gigantic proportions. So often I've looked at American buildings (like the marble public monuments they're still constructing in Washington DC; or the State Capitol in St Pauls, Minnesota) that seem to have vast, gilded quantities of the most expensive raw materials thrown into a rather formless, plagiarised design pot. But the Hoover dam, built in the 1930's, is different. There can't be anything more fluently representative of Art Deco, beautifully executed. What's more, it's functional art; the dam provides vast quantities of electricity from 15 enormous turbines and also regulates the Colorado River. I'm left wondering, along with a native American onlooker standing next to me, how a nation of people capable of this can be so fearful of the outside world. But that's just the point, as you see when you travel off the main route, through an America that so challenges the routine image of a city-society. On my way through the middle of Nevada, across desert between 5,000 and 6,000 feet high, I passed through a continuous film set of the gold-rush days. Sad, decrepit towns of shanties and trailer-homes, all surrounded by rusting junk and ever-present dreams of making the big strike. Places like Goldfield; Tonopah, once the site of a big silver mine; and Austin, 7484 feet up in the Toyabe mountains and overlooking the still-active gold mines of the Big Smoke Valley. You drive by a gallows ("We still hang 'em here," said the man lounging in a shop doorway halfway up Austin's main street), casinos galore (many offering cheap meals and free overnight parking) and large roadside hoardings advertising brothel-ranches ("New Ladies Have arrived!"). Nevada's the only state in the US where brothels are legal. America's more than one place. Route 66, a by-way embodying so much of the romantic Wild West, reminds you as you drive past. I've attached a few pictures that spring from wry, nostalgic American humour. Love

and best wishes,

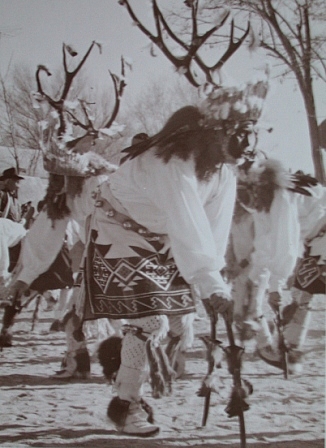

Second Mesa, Arizona, Jan 27. Hello, Friends: It's been a strange week. One day I'm sitting at my own dining table in a spectacularly beautiful new house high above the Arizona town of Prescott, relaxing in ultra comfort. A few more days and I'm sharing a bench in the dusty, high mesa village of Shungopavi with a family of Hopi Indians -- mum, dad, three daughters and several grand-kids -- digging into a steaming bowl of noskwivi (lamb and corn stew, liberally garnished with lamb fat and roasted chili peppers). I'm still running to catch up with a severe cultural challenge. Among the few things Prescott and Shungopavi have in common are American nationality, Arizona soil, brilliant sun and unblemished blue skies -- and SUV's (sport utility vehicles), the new-generation, four-wheel drive cult toys without which the United States would be incomplete. I hope I'm not misquoting him, but I'm sure George Bush said SUV's are good because they enable Americans to get out in the bush spotting terrorists. Anyway, I'm at Prescott, receiving several days of the warmest hospitality chez clients from my days as a furnituremaker at Curthwaite in the north of England. Believe me, it was uncanny sitting on my own oak chairs at my own oak dining-table in the middle of Arizona. (Well, not my chairs and table any more -- you know what I mean). I've been in North America and travelling on Lydia B and the Chevy camper for nearly four years now. First it sent my head spinning backwards. Then a certain pleasure at the trans-Atlantic journey these bits of wood have made, and the link they symbolise between people in two distant places. So -- a week ago now -- having tracked down two lovely little bits of Navajo Indian silverwork containing the palest turquoise from the Dry Creek mine in Arizona's north, I left for one of the Navajos' most revered places, Monument Valley, right on the border with Utah. On the way, I drive through the vast lavafields of Sunset Crater, whose eruptions nearly a thousand years ago re-shaped a vast area of north-east Arizona. Then to the ruins at Wupatki of ancient Indian pueblos -- stone-built, multi-occupant communities -- over the Painted Desert, splashed bright red in vast, distant streaks by deeply coloured rock outcrops crumbling to deep red sand amid the scattered sage, and on past Kayenta to Monument Valley. It's utterly breathtaking. I mean, I've been out in the high desert for nearly three weeks now, rarely parking the Chevy below 6,000 feet each night in all that time. So I'm getting accustomed to these vast, vast spaces of the American southwest. Suddenly, driving the 17-mile dirt road through Monument Valley, I'm in the bottom of an enormous canyon confronting gigantic, statuesque, natural rock sculptures. It's barren, parched, red all around and hard to figure out how the few sage bushes and juniper trees survive. The stillness is rivetting. Navajo live in it. It's easy to see where their religious mysticism comes from. Then I detour back to the Hopi Indian reservation. There are about ten thousand Hopi Indians in a small area northeast of Flagstaff, inhabiting three high mesas in a tight community over a few miles. They're the artists of the First Nation peoples (the name Indians use to remind us that North America really belongs to them, not Uncle Sam). Silverwork, pottery and katsina dolls -- intricate figures carved from the root of the cottonwood tree, painted and dressed to represent spirits inhabiting the nearby San Francisco mountains, and around which all Hopi life revolves -- account for about three-quarters of the tribe's economy. They command extremely high prices to visiting tourists from cultures where hand skills have dwindled to a meaningless trickle. I met Priscilla Nampeyo, elderly potter daughter of a long-famous Hopi potter, in her modest, ramshackle (by the standards of my English culture) little house on the steep road up to First Mesa. She was finishing a new pot, hand-coiled with painted and clay decoration, fired outside with wood and sheep manure. The price? 1,500 US dollars, said without flinching. From what I see of the crafts trade here, she'll probably get it. Wasn't it the white man who invented supply and demand? Soon I'm knocking on Weaver Selina's door at the village of Shungopavi, Second Mesa. The weaver was his father, now dead. Weaver the son turned to silversmithing 37 years ago. There's a neat showroom and workshop in a new, pueblo-style house. There's a fairly new John Deere tractor outside. Like all the Hopi, Weaver's also a dry farmer, growing corn and a few other kitchen crops on unirrigated land -- all of it owned by the tribe. In Weaver's display of overlaid silver, intricately cut with Hopi mystical symbols, I find a ring with a delicately-cut road-runner bird and the lightning symbol, for rain (this area gets between five and seven inches a year, mostly about July). The road-runner is the Hopi symbol for the message-carrier. Seems appropriate. A sale's agreed. I spot a new computer in Weaver's office. Before I know it my camera's out and I'm spending the next three days photographing all of Weaver's jewellery, editing the 150 results on my own lap-top, making a disc and transferring them to his computer, about which he knows little. I explain how to send e-mails to his customers as far away as Japan, attaching pictures; how to use his own new digital camera, and write detailed instructions. Weaver and his Hopi wife Alberta invite me into their home, feed me for these days, talk at length about Hopi life and take me at dawn to January's Buffalo dances in the dusty little plaza inside the ancient village. It's mind-blowing. Groups of dancers elaborately dressed in buffalo skins, Hopi maidens in woven white mantas decorated with multi-coloured geometric designs, white buckskin boots, turkey and pheasant feathers in their long, black hair; boys and young men dressed to represent deer, with kilt-like skirts and head-dresses of antlers and juniper fronds; boys and men with blackened faces, girls a floury white. All dancing a choreographed story to the penetrating chanting and drumming of a group of Hopi men who accompany them as they emerge from their Kiva, the underground ceremonial chambers dotted around the village. It's all urging the spirits to send rain and food for survival. Flat roofs of the pueblo stone houses round the earth-floored plaza are packed with Hopi onlookers. It goes on for two days while the sun is up, with more visiting clan groups representing different spirits and creatures from nearby Hopi villages. It's a time for extended family members and friends to drop in for noskwivi. Sadly, I have no photographs of these incredible scenes. The Hopi are a very private people and ban all photography and recording, even note-taking, in their villages and at religious ceremonies. I'm itching for images, but toe the line in return for this privileged look inside their lives. It's a dazzling, thought-provoking other world about which I was ignorant. It's hard to imagine a culture more coherent and more in touch with its environment. I'm very sad to say goodbye to Weaver and Alberta, though we promise to keep in touch on his new computer. I want to meet more Indian craftsmen and women. Soon, in New Mexico, the Navajo rug-makers, the Zuni jewellers and the Santa Clara potters. Love

and best wishes,

Morenci, Arizona, Thurs Feb 13. Hello, Friends: I'm standing on the edge of the biggest hole in the ground I've ever seen. It's five miles long, two miles wide, about half-a-mile deep and it's in America. (Where else?) It's sunny, but the air's opaque with fine dust and a sort of dislocated hum of many motors fills the whole area, coming from nowhere but everywhere -- I think it's from the tiny trucks I can see crawling slowly along dirt roads way down in the bottom of this pit. It's too far away to make out people. It's uncannily like one of those James Bond movies. You know -- the empire of evil Bond's sent to tackle twice yearly. I haven't seen any armed guards yet (usually jack-booted, cold war East Europeans, weren't they?), but notices warning "Private property. No trespassing. Violators will be prosecuted" cover the area for miles around this little south-east Arizona mountain town. Copper's what it's all about. Morenci is the United States' biggest copper producer. The operation's run by the Phelps Dodge Corporation, the world's Mr Copper. Here's a few impressive numbers: Every day Phelps Dodge moves over 800,000 tons of material. Those tiny trucks have 14-foot diameter tyres and carry 350 tons of ore at a time. So forgive my old-fashioned surprise, stopping at Georgina's, nearby Clifton's newest roadside coffee shop, when I meet Loy, a willowy-slim feather of a young woman, about mid-twenties I'd say, who reveals she drives one of these monster Caterpillar trucks for a living, twelve-and-a-half hours in round-the-clock shifts, for sixteen US dollars an hour. Her boyfriend does the same, only he gets seventeen dollars. He's been with Phelps Dodge a bit longer. They both get company medical cover -- an enormous benefit in the United States, where an average couple outside a company scheme pays about 6,000 US dollars a year for health cover. With no significant public cover, that's uppermost in so many Americans' daily thinking. If there's anywhere to get an insight on what makes the United States tick, it's here in the vast, mineral-rich desert and mountain spaces of the southwest. Morenci and Phelps Dodge for a start. Size-wise, it's off any scale I'm familiar with. The corporation built and owns the current Morenci -- shopping plaza, houses, library, schools, swimmimg pool, hospital and all -- having buried an earlier Morenci town under a waste dump in the hole as the vast operation expanded. They don't go underground for it. They tear the mountainside apart to get it. Gold and silver mining towns -- most of them ghosts now -- I've already described passing through in the Chevy on my round-about way south from British Columbia back to Lydia B in Virginia. This is different. At Morenci, and at the older, now significantly decomposed town of Clifton a bit lower down the valley -- where the copper boom began in the 1860's -- you breathe and eat copper. Copper dust covers the whole area. Vast, flat leaching-beds of waste containing sulphuric acid, hundreds of acres in extent, lie above Morenci. Acid's what they use to extract copper from crushed ore (there's no smelting anymore. Electrowinning's the new process) -- though the company says all the acid's reused and none escapes into the ground-water in the reclamation process. Copper pays the wages. Life here is just different. Maybe less wild now, but it's still the west that Americans poured out of the east over a century ago to seek fortunes in. The characters we in Europe think of as Hollywood creations are thoroughly real for Arizonans. Geronimo, the Apache warrior who fought the newly-arrived Americans over a century ago, is said to have been born at Clifton. (I spent a couple of hours in a lovely little museum at Truth or Consequences, just over the border into New Mexico, looking at Geronimo's documented history. The museum also contains a stunning collection of artefacts from the pueblo Indian cultures. And where else but in the United States would you find a town called Truth or Consequences? Actually, until 1950 TorC, as it's locally known, was called Hot Springs. The town voted to change the name after a national radio show staged a performance there). Then there's the OK Corral, scene of the famous shoot-out by Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday against a cowboy gang. It's a real place at Tombstone, a few miles northwest towards Tucson; Billy the Kid robbed and marauded not too far away; Wild Bill Hickock operated nearby. At Taos, up in the mountains of northern New Mexico where I was until a week ago, staying with Bill and Emily, a furniture-making couple from Washington, there's a Kit Carson museum. Western life, a booming southwest American arts scene and Indian culture sit alongside each other. Clifton's hey-day was in the copper boom of the early 1900's. Once-elegant buildings in Chase Creek, the town's original main street, have been mostly empty and decaying for the last 30 years. Only now are there the first signs of interest in buying and restoring them. All that remains of the Lyric Theatre is an empty, arched facade. Wandering with my camera along the street I met Charles Spezia, grandson of one of the two Italian Spezia brothers who built much of Chase Creek about 1913. The Spezia name's high up in stone on several of the street's neo-classical porticos. Charles retired from his job as a NASA space chemist and returned to live in Clifton. He passed on more Clifton nostalgia during a spicy Mexican meat-ball meal at Basha's up at Morenci, the Lebanese grocery chain that does for the southwest what Tesco does for England. I spend an afternoon with Walter Mares, old-fashioned news-editor of The Copper Era, who digs out for me old copies of his newspaper coverage of floods that devastated Clifton when the San Fransisco River burst its banks in 1983, and of the big copper strike against Phelps Dodge shortly after that, when the company broke the miners' union. And I'm astonished to hear -- so rarely in my US journey -- doubts expressed about the sacred notion of freedom in the United States, admittedly from an active Democrat in the middle of a fairly solid Republican state. This is that sort of place. I'd begun to think nearly all Americans unquestioningly obeyed that official red hand and the injunction "Don't Walk!" at all pedestrian crossings. Then, back at Georgina's (the name's fictitious, but the substance is fact), to complete a routine day. Georgina's mid-forties. She moved here from California less than a year ago when her boyfriend there went to jail. She bought a house (for 17,500 US dollars -- it's different here) and is now struggling single-handed in rented premises to start a coffee and sandwich restaurant. It's tough, lonely work. Her daughter came earlier this month and lasted five days in Clifton. Outside is Georgina's five-ton truck, which she used for her one-woman haulage business. Before that she ran a business serving court summonses in Grass Valley, California; and before that she ran a window-cleaning business. I'm staggered by this enterprise. But this is the American West. It's unremarkable round here. And so the story continues. It seems a long way from the Hopi village back north at Second Mesa, a long way from British Columbia and a long way from Curthwaite, Cumbria, England. Since Second Mesa there's been the amazing Anasazi pueblo Indian cliff dwellings in the Canyon de Chelly and the Chaco Canyon pueblo buildings on the San Juan valley, eerily deserted and still substantially standing a thousand years later. And an overnight dash from New Mexico to Phoenix airport to get a flight to England after news that my mother broke her hip in a fall. Parked on top of Phoenix airport car-park I got news of good progress and reverted to track. It's an awfully big, multi-faceted country, impossible to drive through without looking. I'm learning, perhaps for the first time, to smell the roses a bit. Love and best wishes, Ian.

San Francisco River Canyon, SE Arizona, Thurs Feb 20. Hello, Friends: Take a tin of Heinz baked Beans (vegetarian)............ It's another day in the magic canyon. A week here already and I'm finding it strangely difficult to drive out of this bewitching place. Again tonight the Chevy's parked near the bottom of this age-old valley. The 5.0pm whisky and ginger's come and gone yet again and I'm dining in the dusk on curried bean burritos. There's no-one for miles. KFM-KCUZ (that's 'zee'), the local FM station at Safford, 40 miles away, is playing non-stop country music. They go together, the beans, the canyon and the easy, clip-clop twang with ballads of southwestern daily life. ("Well the lawnmower's broke an' the tax is due... Where we'll get the money, honey, ah don' know." Or the number one theme: "Ah'm still hurtin' from the last time you walked on this heart of mine". Life's straight-forward here). A big, bright moon should be up soon. Forgetting the music and the sound of the nearby fast-flowing river, perennially brown as it cuts deeper through time and the canyon, I could be in a crater on another planet. I've made a quick trip down the five-mile dirt track to Clifton, that faded copper town, and the library at Morenci today to check my e-mails (Ken and Lou somewhere in Texas were just reaching for their five-o-clock ice; Carol & John, homebound from Deltaville Virginia to Melbourne Australia have reached the Caribbean island of Providencia in their boat 'Nerissa'). I get more milk and bread and say hello to Georgina and two local customers at her struggling little restaurant. Another train hauled by three Phelps Dodge company locomotives arrives up Clifton's main street after the steep mountain route to bring supplies or pick up another load of copper. I'm starting to get waves of acknowledgement from passing local truck drivers. Snowbirds aren't pouring into Clifton. They're the generally retired couples who migrate by the thousand from Canada and the United States' north every winter, looking for sun and filling the RV (receational vehicle) parks of the south and south-west. Clifton has one, less than a year old, neatly laid out, each place with water, electricity, outdoor benches, fire and grill with freely available firewood awaiting the steaks. But only two or three of the 38, fifteen-dollar-a-night spaces have been filled all week. I parked the Chevy there on Saturday to re-charge the deep-cycle battery, have a hot shower and watch an Anthony Hopkins video on the on-board TV, paying my fifteen dollars at the local police station. Next day I went back up into the canyon. Clifton -- population about 1,500 (it used to be 5,000) -- is a fascinating place of ordinary working folk, tough mining history and declining architecture, mostly dating from the copper boom of the early 20th century. (Though whereever you go in the Southwest, don't look for posh houses. Most are small, unassuming, mostly trailer-homes or similar, surrounded by old and new cars and domestic junk. Houses are rather more places to live than status symbols). You're as likely to overhear a conversation in Mexican Spanish as one in English. Stetsons, tight jeans and high-heeled cowboy boots are fairly common garb. I get a friendly greeting from Raul Sanchez each time I use his main-street laundry; but I've never seen anyone else there. Business isn't brisk. The RV park, built with federal emergency money after the disastrous 1983 Clifton flood, is an expression of hope; but there's little to pamper mainstream holidaymakers, save for spectacular scenery. Clifton's overshadowed by the enormous Phelps Dodge copper mine a couple of miles up the hill at Morenci, the area's only significant employer. Southwesterners have long lived with the mining industry's potential to create ghost towns. Phelps Dodge is right now cutting back. The price of copper, they complain, has fallen from a dollar and forty cents a pound to seventy-five cents. Among the first things you notice, driving in, are competing roadside signs for three of Clifton's churches. 'The Copper Era', Clifton's weekly newspaper, out on Wednesdays, details services at 14 churches in the two little townships of Clifton/Morenci, ranging from the Sacred Heart Catholic Church (survivor of Chase Creek), to the Shepherd of the Hills United Presbyterian American Baptist and The Potter's House Christian Fellowship. Religion's as fundamental as the environment. I wonder how well Europeans understand that. The 'Era' sheds more light on daily life. The big story lately has been a row between Clifton Mayor DD McCullar and police chief Richard Stockton, suspended last November after initiating a series of drug-related arrests. There are popular demands for the mayor to resign, but he won't. Views are expressed with little apparent concern for libel laws. This is free-speech territory. No polite duelling etiquette with rules and sidesmen.You shoot from the hip here. In Britain we take more time -- and hope the problem goes away. It occurs to me that George Bush comes from another old gun-slinging state. Schools at nearby Duncan face a budget cut of 120,000 US dollars, the 'Era' reports. News editor Walter Mares reports an interview with schools superintendent John Payne. There's this disarming bit: "Payne looked tired in a pre-meeting interview. He said he had not been sleeping well lately as he wrestles with the school's dismal financial outlook." Not much stiff-upper-lip here, I think to my British self.. I go along with Walter in his reporter's coat to a public meeting about a new community project. It's about support to convert a donated building in Clifton into a youth and community health centre to be run by SEABHS ('seabus', somebody said) -- the South Eastern Arizona Behavioural Health Services Inc. Clifton really is at the fag-end of public wealth and health. I'm impressed by the turnout and the community enthusiasm, and puzzled that an area that digs so much wealth out of its ground manages to benefit so little from it. Part of the reason, I'm told, is that Phelps Dodge only manages to get by on cheap Mexican labour. A wide dirt road leads into the San Francisco river valley, built in days of hope for a visitor boom thirty years ago, never finished and abruptly abandoned. Local people call it the "million dollar road". It ends in a wilderness. Quite where it was going no-one seems to know, except Phelps Dodge was keen on it. I'm first driven there in a ricketty 1969 truck by Raul Lopez, a friendly, 70-year-old Spanish-speaker born at Clifton. He spent his childhood in the canyon. He retired, returned and runs an ice-plant now. We stop every few hundred yards as he nostalgically points out favourite swimming, hunting and playing places in the canyon bottom, and the now-defunct gold-mine. You don't go far round here without seeing one of those, either gold or silver. I go back next day....... and the next and the next, biking, walking, driving. It's impossible to ignore the power of the calm in the canyon, and the huge sense of time. It's taken millions of years to form. The area's part of the Gila (say 'heela -- it's Spanish) geological system. You amble by the river picking up stones with traces of turquoise, fire agates, fossils and a whole variety of interesting bits of rock. You're surrounded by multi-directional rock formations telling the story of some enormous past geological upheaval. You scan them -- looking for gold. That's the thing about this place -- there's always the sense that riches are there, somewhere. All you have to do is be lucky. And if you're not lucky, you can breakfast by the river, deep in the canyon. The only sounds are the flowing stream, chirping little dipper-type birds scooting from bank to bank, the crunch of my toast and marmalade and the slow ticking of Lydia B's Radio Shack clock. It's the same tick I've heard all the way down the Pacific, through the Panama canal, up through the Caribbean and into the North Atlantic. How many ticks, I wonder, since this Arizona canyon began? I stick a powerful bear-spray in my trouser-pocket. I haven't seen any yet, but I'm told there are bears, mountain lions and wild pigs round here, besides a whole variety of deer and antelope. I find a few spent cartridges, but no blood. I watch where I put my feet, even though rattlesnakes are mostly still hibernating. I'd quite like to see one -- though preferably hear it first. I've been on a wild goose chase, too. For days I've been studying what I felt sure was a fossil tree at the site of those road excavations. The imagination ran wild. I saw wood features in the grey rock that reminded me of the trees I worked with in England. Funny, but it wasn't in any of the guide books, and no-one here knew anything about it. I went to the geology department of Phelps Dodge up at Morenci, with a digital photo on a floppy disc. I was looking, they said when they opened it in their computer, at a dyke of rhyolite, once-molten rock forced up through a hole in the surrounding rock by volcanic action twenty-two and a half million years ago. Ah, well! I had a free geology lesson. It was fun while it lasted. Love

& best wishes,

Greenboro, North Carolina, Wed, March 18. Hello, Friends: I'd intended this to be datelined Curthwaite, Cumbria, England. As you see, time was the victor and I'm now back in the United States. Tomorrow -- insh'Allah -- maybe tonight -- I should be back on Lydia B a few more miles up the road in Virginia. It will be a haven, as I'll explain. About this time on Monday night (sevenish, just after dark) I was standing in the middle of a frantic evening rush-hour motorway in Atlantia, Georgia chatting to a young black man and wondering if my grip wasn't slipping a little. Rush-hour traffic on interstate 85 was parting round us, screaming by on both sides and the black cop sitting in the patrol car behind, blue light still flashing, seemed to be taking an awfully long time talking to base. The emergency service van had gone. The young black man was personable -- a business management student -- and remarkably pleasant, in view of the fact that I'd just run my three-ton Chevy into the back of his smart, black Toyota SUV. Nobody was hurt. The young man's car was quite unmarked (I can still see it approaching in slow motion and hear the crump. 'Oh, shit!' was what I said. I'd been moving to an outside lane, struggling with flight tiredness and continental disorientation, looking in the mirror while traffic ahead came to a stop) and the only remaining mark, leaving aside my pride, was a dent in the Chevy's front bumper made by the young man's tow-bar. It was a strange sort of out-of-body experience. Here I am, newly off a transatlantic flight after yet more goodbyes to friends, family and familiar places, struggling into a new -- or is it old? -- scene, brain lagging and clearly still on the left-hand side of the road, wondering mainly how on earth I was going to summon enough remaining brain to get out of this lethal spot. And looking at myself talking to him, and imagining him telling his friends there was this old English geezer, as I'm telling you about this nice young black man. Well, I needn't have wondered. The cop finally booked me, stuck a yellow ticket in my hand, returned my strange English driving licence (it looks more like a credit card, but the point is, it's English -- and that's authoritative stuff here), said were were free to go and shepherded both of us safely back into the hurtling traffic stream. We disappeared into the six-lane traffic lunacy and I sought the safety of a rest area for the remainder of the night a few miles down the interstate, much too tired to sleep. I'm feeling like a theatrical scene-shifter changing for yet another production, detached and on automatic. By tomorrow I'll have driven right round the United States since November, from sea to desert to mountains, cities to deserted deserts (not all are empty) -- the equivalent of half-way round the world (and I've only nibbled at the edges); then up and down Britain from friend's funeral to family and friends, to sixty-years ago places and back again. I had a haircut at Lewthwaite's, the barber's in Denton Holme, Carlisle I went to in short pants, perched on a plank on an armchair. It hasn't changed a bit in all the time since, save Alan the barber's just retired and handed over to Margaret (Margaret, a Denton Holme barber?!). The old notice is still on the wall -- "Boys ninepence, men one and thruppence'. Somewhere under the latest coat of thick, bubbly green paint is the coat that was there in 1945. One minute I'm at Tesco's in Lancashire, England putting the hire car through the power-wash to scrape off Solway mud (" 'ave yer dun it before, luv? D'yer know 'ow it werks?"). I've spent two months on both sides of French and English Canada and now I'm trying to clear enough head-space to sail Lydia B, my seaside home for the last four years, across the Atlantic; five hours one way, a month the other. Next minute I'm off the plane in the US getting milk for a desperately wanted cup of tea at a corner store in a mainly black Atlanta suburb, thinking they all look a bit tough and the place scruffy and uncared-for, then noticing the shop assistants are behind an armoured glass window. I assume these days there's some genie protecting me. A month in a monastery sounds a neat idea (assuming it doesn't turn out to be a month in an Atlanta jail). So what's it all about? I really meant this piece, the last of the Lydialogs on this current North American trip, to dwell on the why? I get snatches of that question from time to time -- usually the nearer England the more oblique it is. From some, including my family, I get the feeling I'm nuts or something slightly sillier, to have given up a nice house and a hard-won business in leafy England to go wandering about in strange, sometimes uncomfortable places in a boat and a Chevy. (Which is odd, when you come to think of it, in a nation with litle to lean on but centuries of hugely successful piracy around the world). Not quite so with friends in Canada and the USA -- and that's the thing that really fascinates me. I did it not because it's there (that's the unilluminating, dead-end answer we English give to why Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tensing and the like struggle up impossible Everests) but because I really want to know, from the roots up. It seems a nice time (sixteen hours to go to George Dubyuh's deadline to Saddam Hussein to quit Iraq or face war) to think about why things really happen. So there I am, in left-hand aisle seat 49C of Delta 065 Manchester to Atlanta, middle of economy class Boeing 777, introducing myself to my four fellow passengers in the row. They're all charismatic Christians from the Brownsville Revival School of Ministry in Pensacola, Florida -- on my right Joanne, a pretty, red-haired 24-year-old with specs and not a few spots (like mine), next Kate, the only English girl of the four (who I gather gravitated to Charisma via drugs), middle-aged Sandy who seems to be the leader and twenty-odd-year-old Ryan, with black travel-stubble.. Sooner than you know it we're all holding hands at 40,000 feet in mid-Atlantic while Joanne says prayers before we all pile into Delta lunch (chicken and awful, gooey rice. Obviously the wrong prayer). The conversation's entirely about God -- theirs, but so far not mine, I tell them. Which serves only to provoke a serious onslaught to persuade this ageing sinner to let God in. Only those who do will be saved. But I'm only there to listen and provoke. What about, I ask, all the world's Bhuddists, Confucianists -- and not least pertinently -- all those muslims from Iraq to Indonesia and beyond? Any chance for them, too? Total blank here. If you don't believe, you're lost. It's pretty much the same message I've picked up many times on this US journey, listening to the proliferation of FM Christian radio stations and particularly driving through the south from Arizona across Texas, Arkansas, Mississippi, Georgia and now the Carolinas. Churches abound and Americans go in numbers that must make Dr Williams, the newly-installed boss of the Church of England, green with envy. It would be unfair to suggest there isn't a wide diversity of religious beliefs and tolerances in the United States, but for the life of me I can't see enough difference between Islamic fervour and the fervour (I shy at the word 'extremism') I've just experienced in row 49. However, the plane lands safely through ground-level cloud at Atlanta, we get off, hold hands for more prayers at the baggage reclaim and say goodbye, me armed with Sandy's newly published book "A Revelation of the Lamb for America" and wishing my companions well. Perhaps Osama bin Laden's written a parallel book for the lamb of Iraq. I'm alarmed, and wondering what's changed since Richard the Lionheart set out on his Crusade. Still, not for me to wonder. I'm just an observer at life's football match. The kick-off's pretty soon now. I'm just glad I've got a comfortable ring-side seat. And talking of the English, I've been reading a wonderful insight -- same title, "The English" -- on us strange, screwed up lot by Jeremy Paxman, the British TV journalist. It should be compulsory reading for every Brit who thought (like most of America, it sometimes seems!) that the world still owes us a living. Love and best wishes, Ian.

Introduction 0 - Inside Passage and northern British Columbia 1 - British Columbia to El Salvador 2 - Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama 3 - San Blas to Florida 4 - Intra-Coastal Waterway to Washington DC 5 - Brentwood Bay BC and Chesapeake 6 - Virginia & Atlantic to Azores 7 - Azores & Ireland to England 8 - Chevy through the US - 2

|